Cecil Cahoon, SC Progressive Network Education Fund Board

One hundred thirty years ago on May 11, 1894, unionized workers of the Chicago-based Pullman Palace Car Company walked off their jobs in protest of 25-percent wage cuts, terrible working conditions, and 16-hour workdays. Company owner George Pullman was their employer and landlord, as most workers lived in company-owned housing, but Pullman kept rents high and refused to hear workers’ grievances. Nor would President Grover Cleveland, who ordered federal troops into Chicago not to keep the peace but to ensure that trains continued to run. When striking workers reacted predictably, Cleveland’s National Guardsmen fired into the crowd, killing at least a dozen and injuring dozens more.

The public sympathized with the striking workers against their abusive and powerful employer, which turned the strike into a political problem. By the end of June, Congress passed and Cleveland signed an act establishing a federal holiday known as Labor Day to honor America’s working class every first Monday in September.

Here in South Carolina, the plantation model of labor management had already been perfected in the textile manufacturing industry, with its class stratification and mill villages evident in every population center of the state. Mill owners built the stores, schools, and churches in their villages, even hired the pastors and teachers and dictated what sermons and lessons would be preached and taught in them. They owned the tracts of rental houses where their employees lived, and they supplied the electricity and gas to those homes. So the meager wages paid to workers came back to the mill owners in rent or payment for groceries, clothing, and everything else.

Every aspect of life was determined, provided, or withheld by a consortium of mill owners according to their preferences, and the result was a permanent under-class of working poor. The model was so woven into the fabric of the state that political leaders trumpeted South Carolina’s “cheap labor” from advertisements in northern periodicals to speeches on the floor of the U.S. Senate.

From Cleveland’s announcement of the first Labor Day holiday through the next forty years, union organizing among South Carolina’s working class was suppressed by all legal means, and by extra-legal means when necessary. Depression-era conditions led workers to strike in protest of the “stretch-out,” a system that increased production while decreasing wages. But no state or federal law existed to protect the rights of workers against employers.

So when workers at Honea Path’s Chiquola Mill joined in the textile workers’ strike that swept from northern Alabama through Georgia and the western Carolinas in the summer of 1934, it was an act of courage. In a mill town as small as Honea Path — population 2,750 — where everyone knew everyone, where Mayor Dan Beacham was also a steward at the local Methodist Church and the mill superintendent, striking workers knew they could be fired with impunity, and that scabs — non-unionized workers who were also their friends and neighbors — could be hired to take their jobs.

What they didn’t expect was to be assassinated by their employer, killed by men they knew personally at the orders of their manager.

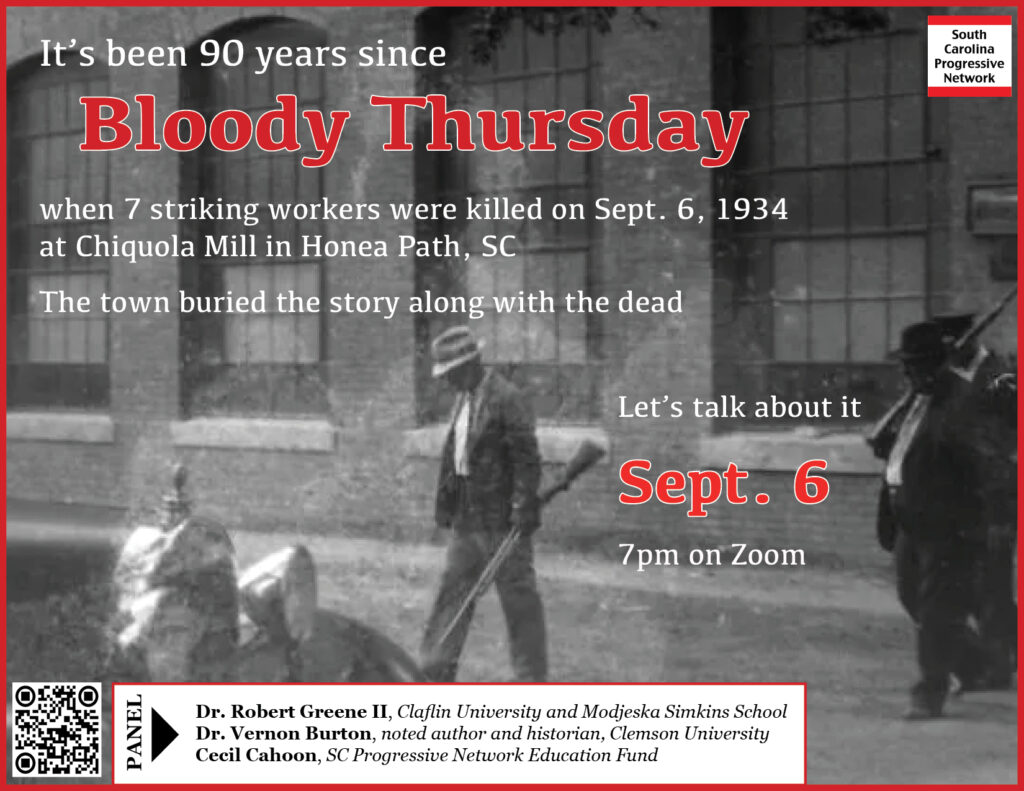

This September 6 marks the ninetieth anniversary of the Honea Path Massacre on Bloody Thursday, when seven Chiquola Mill workers were murdered in broad daylight for the sin of striking for better wages and working conditions.

On that Thursday morning in 1934, as non-unionized workers on the night shift left the property and more arrived to begin the day shift, unionized workers gathered with family members and allies in front of the mill to continue their protest. None was armed; each picketer was searched by union organizers to ensure a peaceful protest. Before 8 a.m., the crowd had grown to more than 300, including some women. Each side shouted questions and comments at the other, with one argument between two men turning briefly into a physical fight.

But earlier that day, Beacham — the mayor and mill superintendent — had deputized and armed 138 men, and had stationed these “special deputies” inside the mill’s second-floor windows. Beacham did this, he said, at the instruction of Governor Ibra C. Blackwood, Sheriff W.A. Clamp, and Adjutant General James C. Dozier.

In the inquest that followed, no one could determine with certainty who fired the first shot from the mill windows, but the shooting continued for several minutes as striking workers turned and fled in all directions. Three of the workers were shot in the back. Clamp and Deputy W.J. Watson were present outside the mill, but Watson later told the media that none of the law enforcement officers present “so much as drew a gun” in the melee.

When the shooting ended, scores of striking workers lay wounded and bleeding in the street, on the sidewalk, or in yards across the street from the mill. Six men were dead: Claude Cannon, 25; Lee Crawford, 26; Ira Davis, 26; E.M. (Bill) Knight, 45; R. Thomas Yarborough, 45; and Maxie Peterson of Greenwood, 25. Two days later, another victim would die of his wounds: Charles L. Rucker, 35.

No weapons were found on any of the slain men.

As the ambulances arrived to take the wounded to the hospital in Anderson, 18 miles away, and Coroner J. Roy McCoy arrived to survey the dead, Chiquola President L.O. Hammett closed the mill for the day. From Columbia came notice that Governor Blackwood had ordered Company D of the 118th Infantry to Honea Path — not to protect citizens or keep the peace, but to protect Chiquola Mill from potential harm.

The funerals couldn’t be held in the churches of Honea Path because they were owned by the mill, W.A. Smith, who was wounded that day, told reporters 60 years later. Instead, open-air services for the first six victims were held on Saturday in a field at the edge of town, with an estimated 10,000 people attending. TIME magazine covered the event. Services for the seventh victim was held on Monday.

L.E. Brookshire, president of the South Carolina Federation of Labor, declared that it was a “cold-blooded attack on unarmed pickets exercising their constitutional rights.”

Chiquola Mill re-opened for normal operations on Tuesday morning.

One week later, a total of 317 witnesses were summoned to testify at the inquest, including 207 named by the state, and more than 90 testified. They included women widowed by the assassinations, the wounded son of a murder victim, and three physicians who attended the scene. Witness Annie May Davis was the wife of victim Ira Davis and the sister to victim Lee Crawford. Witness Jim C. Fox testified quietly and haltingly due to a neck wound.

Through questioning under oath, Solicitor Rufus Fant determined that the shooters included Chief George Page and Officers E.T. Kay and Charles M. “Big Charlie” Smith of the Honea Path Police Department, and “Special Deputies” Robert Calvert, Lev Young, Tom Stalcup, Rob Smith, Lawrence Smith, and Claud Campbell — a 15-year-old boy armed with a .22 rifle.

According to multiple witnesses, Crawford was shot three times in the back from a yard’s distance after Crawford had been knocked to the ground. A physician confirmed that Crawford bore powder burns from being shot at close range, and that Yarborough and Knight were killed by buck shot from a shotgun.

In his testimony, mill superintendent and Mayor Beacham reported that he left the scene before the night shift departed the mill and the shooting began, went home to have breakfast, and only returned to the mill after the shooting had ended.

The hearing lasted two full days. In his summary report to the jury of nine, Fant counted the dozens of witnesses who testified that Officer “Big Charlie” Smith and Calvert shot Crawford; Officer E.T. Kay shot Yarborough; Chief George Page shot E.M. Knight; Claud Campbell shot Cannon; and Officer “Big Charlie” Smith shot Davis. The jury deliberated an hour and sixteen minutes before returning to hold the named shooters responsible for the deaths.

Fant issued warrants charging murder on the parts of Page, Smith, and Kay of the police department, and “Special Deputies” Lawrence Smith, Calvert, Campbell, Stalcup, James Smith, Floyd Smith, and Rob Smith.

In November, a grand jury indicted only Officer Charles M. “Big Charlie” Smith and “Special Deputy” Robert Calvert, finding insufficient evidence to indict the other named shooters.

At trial in the county seat of Anderson the following February, Smith testified under oath that he never took his gun out of its holster during the shooting. Calvert swore he “was not conscious” of having fired his pistol, and that two of the slain men had grabbed and beaten him until he passed out. He assured jurors he regained consciousness only after the shooting was over, and realized after returning home that his pistol had three empty cartridges in it. He denied having shot anyone.

Twenty-two witnesses for the state testified that Smith and Calvert had shot strikers without provocation. Eighteen witnesses for the defense testified that Smith and Calvert had only fired their weapons in self-defense.

Beacham, who told reporters after the shooting that he’d “deputized” 138 men on instructions from the governor, the sheriff, and the adjutant general, conceded under oath that he’d “deputized” the shooters without the approval of Honea Path city council but asserted that the “special deputies” were “sworn in to keep the peace through the town.”

After four hours of deliberation, the jury acquitted both Smith and Calvert.

In the weeks following the massacre, “the town rolled up,” said one resident.

By the end of September, union leaders called off the strike due to “force and hunger,” and when strike funds had run out.

Claude Cannon’s widow, Iona, had six small children and no income, and she lived in a rental house owned by the Chiquola Manufacturing Company. She didn’t earn enough from her job at a local shirt plant to pay the rent, power, and fuel, so the Chiquola owners sent her an eviction notice when the debt reached $115.55. She was given two weeks to vacate the premises.

Then the Chiquola owners offered her a job in the mill where her slain husband had worked, with two caveats: She could work for Chiquola as long as she wished, so long as she paid the back rent and she never mentioned a union. With children to raise and no options, she took the offer.

For decades, Iona Cannon kept the clothes her husband was wearing when he died.

For the next sixty years, no one talked about Bloody Thursday. When documentary filmmakers George Stoney and Judith Helfand began research for a film, Elaine Ellison-Rider of The Belton and Honea Path News-Chronicle published an article on the project and was warned by readers to “let people forget.”

“They were still scared after 60 years,” the reporter wrote. When the strike ended, workers had no alternative to going back to work in the same mill. Children and grandchildren of the murdered men wounded up working at Chiquola Mill if they stayed in Honea Path.

The resulting documentary, “The Uprising of ‘34,” stirred a few descendants to take action and raise funds for a monument to honor the slain men. At an event in May, 1995, Claude Cannon’s daughter and grandchildren saw a granite marker unveiled by Dan Beacham’s grandson, author Frank Beacham. The younger Beacham had been born and raised far from Honea Path and became involved only after learning from the filmmakers of his grandfather’s role.

Chiquola Mill’s new owner, Springs Industries, provided a $440 meat tray for attendees at the public service.

But the documentary also illustrated the immoral lessons that the massacre taught South Carolina’s working class: that workers should be grateful for their employment, should accept the wages and working conditions provided for them, and should expect and ask for nothing more.

Worse, if they attempt to organize through a union to improve the quality of their lives, they should know that their employer could take their livelihoods and their lives with impunity. No justice will be available to them forever. And the state of South Carolina would offer its working citizens no protection from their economic and political superiors.

Those economic and political superiors weighed in one last time to reinforce these immoral lessons when the documentary was released. Decision-makers prevented its broadcast on South Carolina ETV on June 27, 1995, the night that it aired on public television stations nationwide.

SCETV President Henry Cauthen denied that the film was censored for its content. Spokeswoman Kathy Gardner-Jones called it “an editorial decision” and explained that the program department believed “that this film didn’t represent overall community wishes of what they wanted to see.”

SCETV refused to air the documentary for three more years until June, 1998.

One way to honor Labor Day this year is to view “The Uprising of ‘34.” Another is to visit Honea Path and see the marker in Dogwood Park, a short distance from the former site of Chiquola Mill and the murder scene. The abandoned mill began crumbling in 2009 and was demolished in 2018.

Yet another is to seek out and thank the courageous men and women who are dues-paying members of their unions in South Carolina, living and working in defiance of a political and economic system designed to keep working South Carolinians productive, compliant, and unable to threaten the state’s power structure.

Perhaps the best way to honor this Labor Day is to join them in their struggle for better lives.

• • •

Please join us for a virtual program on Friday, Sept. 6. Scan the CQ code in the flyer or click HERE to register. All are welcome.

•