Building on the work done since the SC Progressive Network‘s forum Corruption in the Palmetto State last May, we want to go beyond identifying the problems in our ailing democracy to focus on remedies, both legislative and cultural.

Building on the work done since the SC Progressive Network‘s forum Corruption in the Palmetto State last May, we want to go beyond identifying the problems in our ailing democracy to focus on remedies, both legislative and cultural.

The Progressive Network’s Education Fund has written five bills that have been introduced by our partners in the Progressive Legislative Caucus that address campaign finance and corruption. Another bill is in the works that focuses on the fact that 77 percent of SC voters have only one name on their general election ballot for their House and/or Senate representative. Our politically gerrymandered districts facilitate corruption through lack of competition. Only 8.6% of the state’s registered voters elected the Republican majority in the 2016 primary election.

All the bills filed to date calling for an independent redistricting commission fail to make the commission truly independent as they are appointed by the Governor and the legislature and default to the legislature if the “independent” commission fails to reach a decision. We will be introducing a bill for a Citizens Redistricting Commission this session, along with a constitutional amendment to let the citizens draw the districts, not the incumbents.

We are working with Republican legislators on other bills they have introduced to make our campaign finance system more transparent and accountable.

• • •

S-533 (Sen. Mike Fanning, D-Fairfield and Rep. Cobb-Hunter, D-Orangeburg) would make politicians removed from office due to a criminal conviction pay for the special elections to replace them. The millions in corporate campaign cash to legislators who face no opposition has contributed to corruption. Each special election to replace incumbent state legislators removed from office due to a conviction costs taxpayers between $35,000 to $125,000, depending on the district and whether it’s a senator of representative being replaced. A special election for a US congressman can run up to $500,000. Since these costs are split between state and county taxes, the constituents of the convicted politician pay the greatest share

H-4443 (Rep. Clary, R-Pickens) requires candidates to disclose if they, or an immediate family member is paid by a company that lobbies their office. A current campaign finance report must be filed 72 hours before and election, campaign expenditures are clearly enumerated and accounted for and independent expenditures are restricted.

H-4444 (Rep. Clary, R-Pickens) prohibits an elected official from appointing a campaign donor to a public office for four years after the donation.

H-4498 (Rep. Cobb-Hunter, D-Orangeburg and Sen. Fanning, D-Fairfield) calls for giving qualified candidates for attorney general who refuse all private donations a publicly financed grant to run for office. In his last race, state Attorney General Alan Wilson took maximum campaign contributions from SCANA, and has taken more than $500,000 from lawyers and off-duty lobbyists in his last three campaigns. Public financing would allow candidates to run for attorney general without taking any campaign contributions from individuals or corporations that may later need to be investigated or indicted. In 2001, then Republican Party Chair Henry McMaster understood the problems inherent in allowing the state’s top law enforcement officer to rely on private cash to run for office. McMaster told Gov. Hodge’s Campaign Finance Reform Commission that the race for attorney general is the one elected office that should be publicly financed.

H-4499 (Rep. Cobb-Hunter, D-Orangeburg and Sen. Fanning, D-Fairfield) places a constitutional amendment on the general election ballot that lets the people vote to allow public financing for Attorney General candidates.

H-4501 (Rep. Cobb-Hunter, D-Orangeburg and Sen. Fanning, D-Fairfield) would prohibit regulated utilities from making campaign contributions to the candidates and politicians who regulate them. An example is the 2007 legislation that allowed SCE&G to charge ratepayers in advance for nuclear reactors that have since been abandoned.

H-4500 (Rep. Cobb-Hunter, D-Orangeburg and Sen. Fanning, D-Fairfield) would place a small fee on all campaign contributions that would fund an automated public disclosure system and generate money for attorney general candidates who want to opt into a publicly financed campaign. The State Ethics Commission is woefully underfunded, short-staffed, and has a public disclosure web site that is opaque. Furthermore, candidates make unintentional mistakes – as well as intentional – in filing. This bill offers a low-cost, high-tech solution to multiple problems. S-766 requires all campaign contributions to be deposited in interest bearing accounts with the interest going to the benefit of the State Ethics Commission.

H-4456 (Rep. Clary, R-Pickens) is a bipartisan bill calling for a committee of non-elected citizens to draw district lines for the legislature and US congressional districts. Redistricting is a critical part of restoring democracy in SC, and the process is an earnest work in progress. Consider: 77% of SC lawmakers are elected with no opposition in the general election. Just 8.6% of the state’s registered voters chose the ruling majority of the General Assembly in the Republican primary.

S-764 (Sen. Timmons, R-Greenville) makes candidates tax returns available to the State Ethics Commission during an investigation or complaint.

S-765 (Sen. Timmons, R-Greenville) redefines lobbyist to include those work, without compensation, for another party to influence official actions.

Questions? Contact the Network at 803-808-3384, network@scpronet.com.

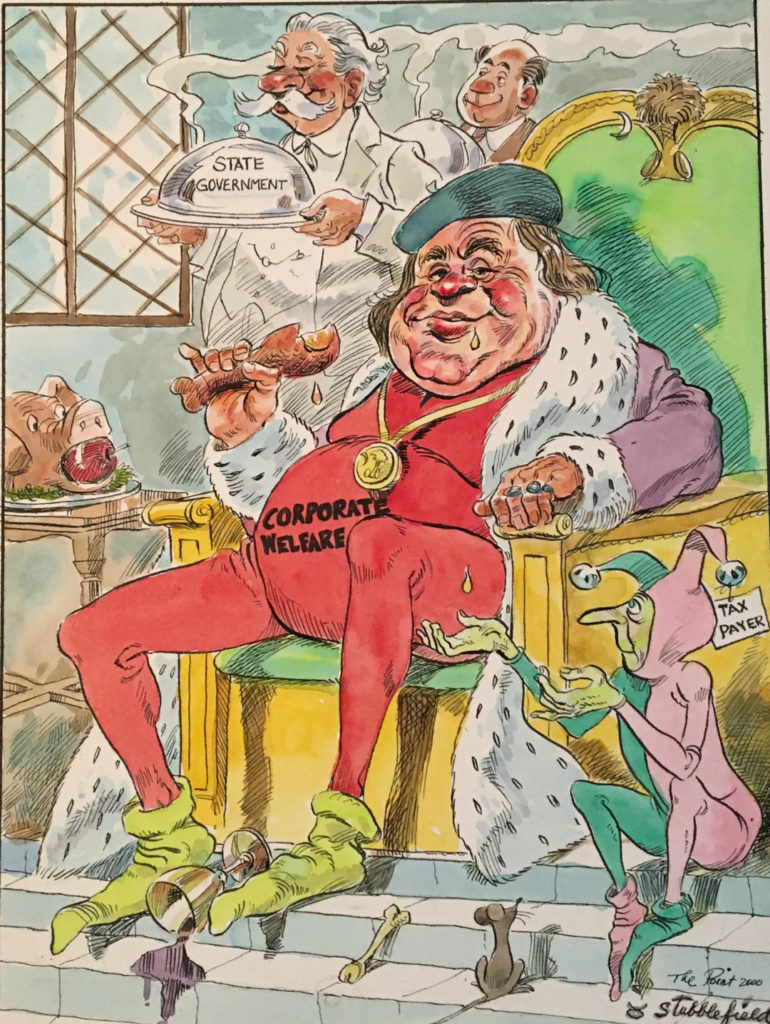

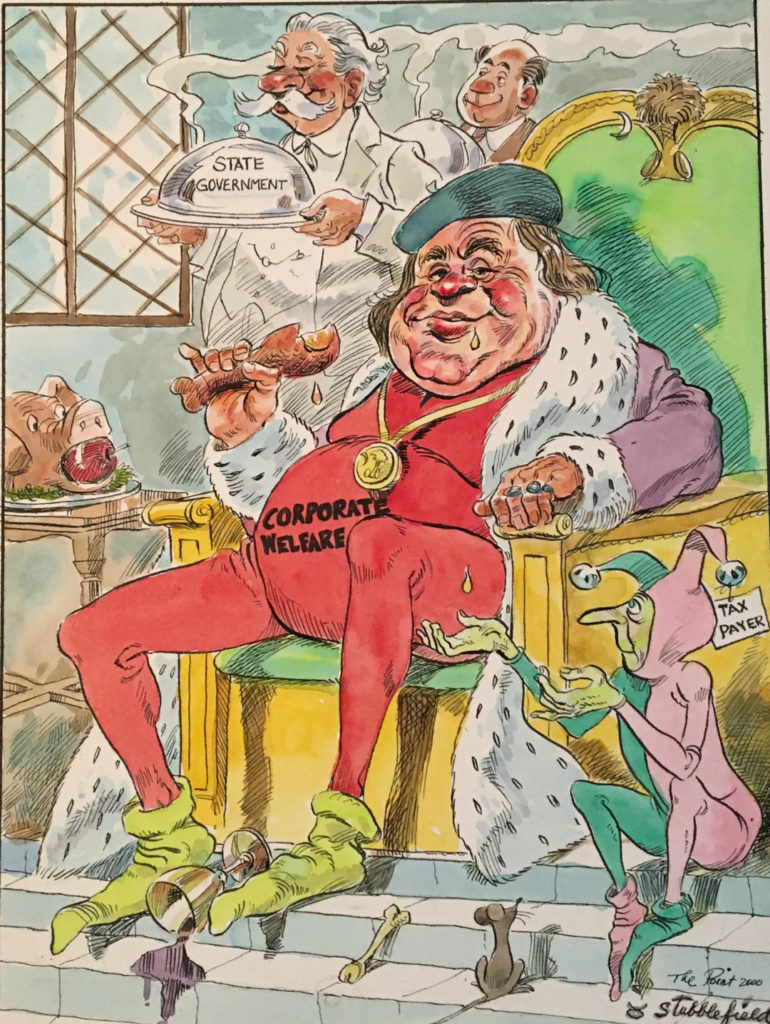

It is worth noting that Sandifer is also a Task Force Chair of the uber-business friendly American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).

It is worth noting that Sandifer is also a Task Force Chair of the uber-business friendly American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).