Author Archives: Becci

Election protection workers share hotline number with SC’s early voters

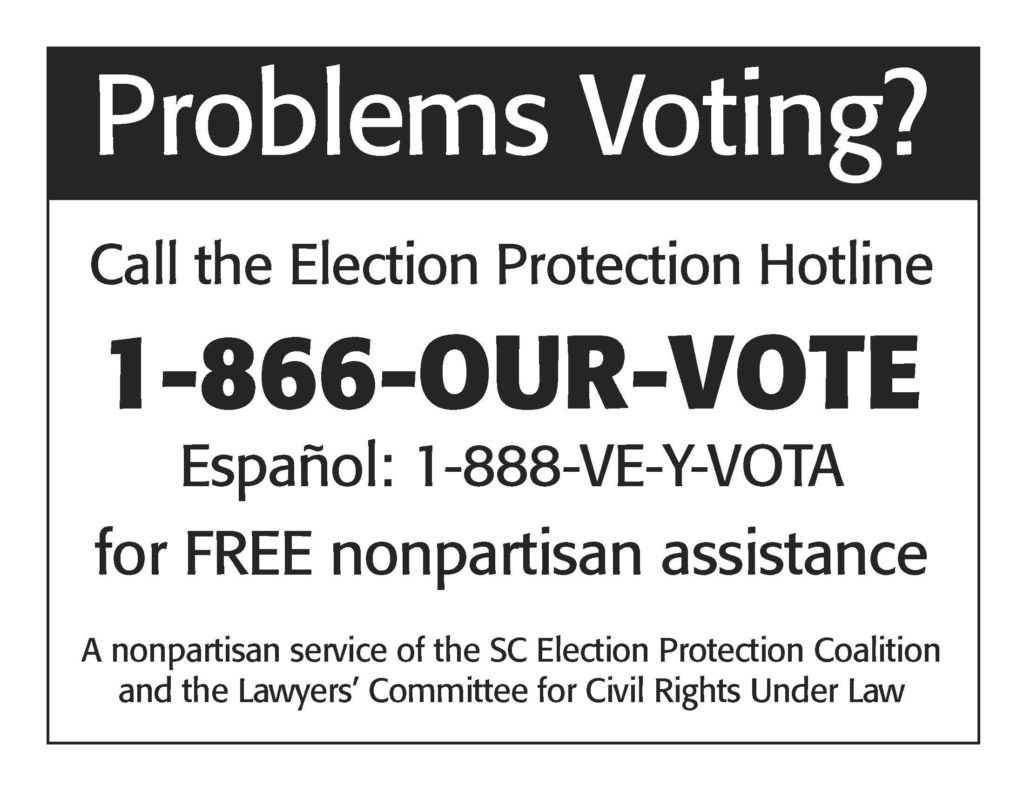

Heading to the polls? Keep this number handy: 866-OUR-VOTE

A nonpartisan hotline is now live for voters in South Carolina who have voting-related questions or want to report problems they experience or witness at the polls.

The Election Protection Coalition, in alliance with in-state nonpartisan organizations, is working to ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to vote in South Carolina. In addition to the 1-866-OUR-VOTE hotline, trained nonpartisan volunteers will be on the ground across the state to provide voters assistance at the polls on Election Day.

“This will be the 12th year that this free, nonpartisan service has helped South Carolina voters with problems at the polls,” said SC Progressive Network Education Fund Director Brett Bursey. “Beyond providing help to voters, reports to the hotline provide the only nonpartisan, real-time, statewide audit of the state’s election system that helps identify problems to address before the next election.”

By calling the hotline, voters can confirm their registration status, find their polling location, and get answers to questions about proper identification at the polls.

Voters who have been required to vote a provisional ballot should call the hotline for advice prior to the certification hearing on their provisional ballot that take place in each county’s election office on Nov. 6.

“Voters must be aware that the state’s photo ID requirements will be enforced for voting in person at all locations” said Susan Dunn, attorney for the ACLU of South Carolina. All voters are required to show a valid ID that includes: driver’s license, DMV-issued ID card, passport, concealed weapons permit, federal military ID, or their photo-voter registration card with them to the polls on Election Day.

Dunn said, “We recommend to voters without one of the accepted IDs to trade their paper voter registration card in at their county elections office for one with a photo on it.”

YOU can help protect the vote in South Carolina

Join SC ACLU attorney Susan Dunn and SC Progressive Network Director Brett Bursey for a training on Zoom to help protect voters in the upcoming election. Trainings will be held on Oct. 10, 15, 19, and 24.

Volunteers will monitor polling locations, direct voters with questions to the national Election Protection hotline, and report concerns to local election monitoring headquarters. Due to COVID-19, volunteers will not be asked to go inside any polling place. We will provide masks for all volunteers to wear.

We will work polling locations across the state, with an emphasis on Beaufort, Charleston, Greenville, Horry and Richland counties.

All volunteers are required to attend a 1.5 hour training. We ask that volunteers serve at least four hours on Election Day. No experience needed.

Questions? Call 803-808-3384.

Court to consider SC Progressive Network case to extend voter mail-in registration

Given the unique challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the SC Progressive Network Education Fund has filed suit to extend voter registration beyond the Oct. 6 deadline for mail-in applications in South Carolina.

A hearing before US District Court Judge Mary Geiger Lewis is scheduled for 11am on Tuesday, Oct. 6, in the Mathew Perry Federal Court House in Columbia. The hearing is open to the public with appropriate ID and face coverings.

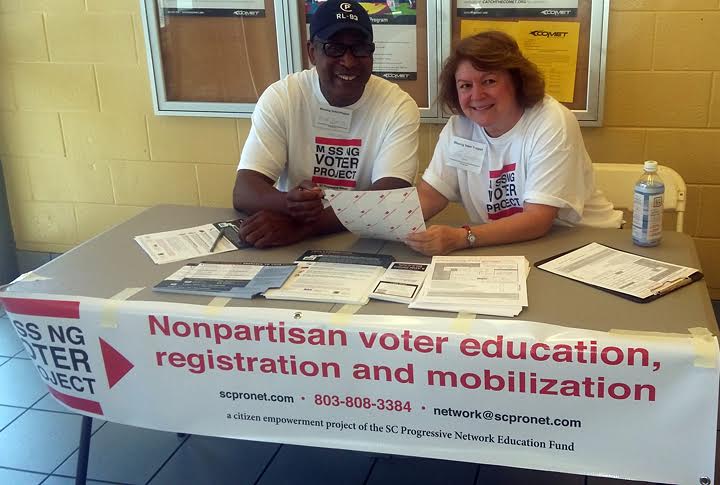

The Columbia-based Network Education Fund, a 25-year-old nonpartisan policy and research institute, has been monitoring the state’s election and campaign systems since its formation in 1996. Since 2004, the Network’s Missing Voter Project (MVP) has been doing voter education and registration in the state’s historically under-represented communities.

Network Director Brett Bursey said, “We are nonpartisan, so we don’t focus on candidates. Our job is to help citizens understand how state and local government policies affect their lives so they can make informed decisions about registering and voting.”

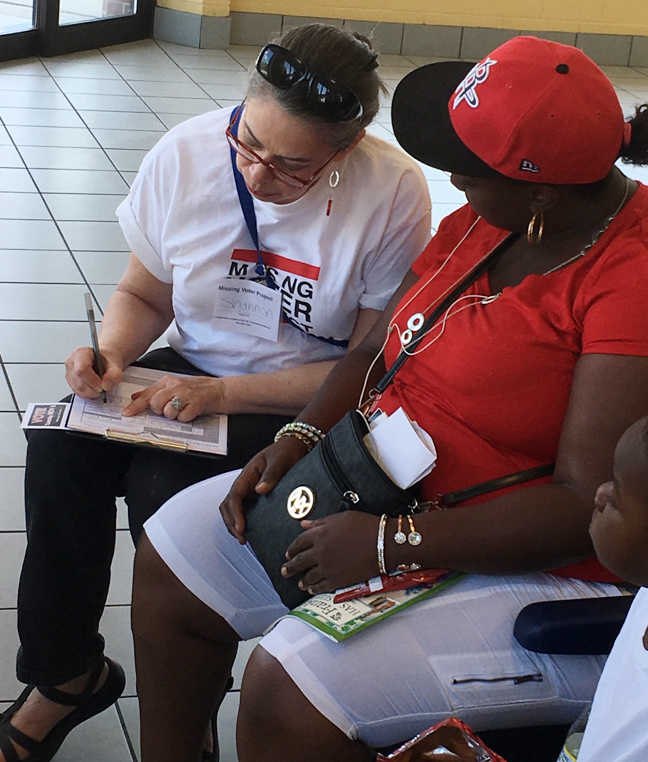

For 16 years, trained MVP volunteers have registered voters at events and locations around the Midlands, several thousand in each presidential election year. This year, the MVP partnered with the SC NAACP State Conference to train young Black members on nonpartisan registration practices in 26 counties. Those grassroots efforts were complicated by the pandemic and our commitment to keep volunteers and the public safe.

“Since March,” Bursey said, “health centers, bus transit stations, food banks, and schools have been shuttered or restricted, and large public gatherings have gone virtual. As a result, we have registered just several hundred citizens.”

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, South Carolina is one of only six states that close voter registration 30 days before elections. The Network’s complaint, filed on Oct. 2, points out that the current 30-day provision became law in the 1895 State Constitution, which was written specifically to exclude Black citizens from voting. “The 30-day ban was implemented before the age of cars and electronic transmission of voter registration documents,” Bursey said. In 26 states, citizens may register and vote on the same day.

The complaint notes that the State Election Commission in the past has supported moving the registration period closer to the elections, citing extensions the SEC has provided due to hurricanes. “There is no doubt that pandemic safety measures and government restrictions have prevented some citizens from registering and participating in the next election,” Bursey said.

The SC Progressive Network Education Fund is represented in this case by Free Speech For People; Emery Celli Brinckerhoff Abady Ward & Maazel LLP; and Burnette Shutt McDaniel P.A.

A short conversation about a big idea: fair maps

SC Progressive Network Director Brett Bursey talks with retired Sen. Phil Leventis and Rep. Gilda Cobb-Hunter about the Fair Maps SC campaign to end gerrymandering in South Carolina.

Leventis, elected in 1982, knows better than most how the game is played. “Having been involved in five reapportionments, I can tell you that it is driven primarily by partisan interests — keeping the majority or trying to gain the majority — and personal partisan interests, trying to keep a safe district for yourself. That’s a shame.”

Leventis believes that only citizens can take the politics out of drawing maps. “What we need is the most objective group we can get to design districts with the charge that they be competitive,” he said.

The fair maps plan is a way to do that.

“I’ve seen the fair maps plan, I’ve worked on the plan, and I’ve talked about it with other people, and it is a grand plan. That it is right and good is not enough to carry the day. This plan can compel legislators to take a vote on it. Nobody can compel legislators how to vote except their constituents.”

After two years research conducted by the Network’s nonpartisan Education Fund, Rep. Cobb-Hunter withdrew from redistricting legislation she sponsored in 2016, and introduced fair maps legislation in 2018.

The legislation to create a citizens redistricting commission includes a joint resolution for a constitutional amendment to allow citizens to vote on the matter, letting people rather than politicians to draw district lines. Why the companion bills? “I’m a realist,” Cobb-Hunter explains. “I understand the process. The point of the resolution is to use the statutory authority of citizens to compel their local county councils, to compel the legislature to do things differently.”

History has shown that the legislature will not reform itself and willingly give up the power to draw district maps. The courts have provided no relief when it comes to gerrymandering.

“So for me and the Fair Maps Coalition that I’ve been working with it made sense to say Plan A was the General Assembly, Plan B was the courts, let’s try Plan C, which is the citizens.”

Elected in 1992, Cobb-Hunter is the longest-serving incumbent, longest-serving woman in the SC state legislature, and the longest-serving person of color in the history of that body. “The bottom line is that things have to change,” she said. “People ought to have choices, and the reality is that here in South Carolina voters simply don’t have choices. Competition is not part of our state legislative races, and that’s not good for democracy, it’s not good for the system, and it’s not good for legislators because they tend to focus on a few people in a House or Senate district [who elect them in their party’s primary].”

“The bottom line is that things have to change,” she said. “People ought to have choices, and the reality is that here in South Carolina voters simply don’t have choices. Competition is not part of our state legislative races, and that’s not good for democracy, it’s not good for the system, it’s not good for legislators because they tend to focus on a few people in a House or Senate district.”

Voting in the age of COVID: what you need to know

Voters in South Carolina already have topped the record of 140 thousand by-mail ballots cast in the last general election, the State Election Commission said today. With 10 weeks to go before the November elections, the SEC has received more than 160 thousand applications for absentee ballots.

The SEC also reported:

• All counties will be open on Sept. 28 for in-person absentee voting.

• Over a third of the counties will open extension offices for in-person absentee voting and by-mail ballot return.

• Drop boxes will be available at many county voter registration offices and extension offices. A list will be released by Sept. 28.

Reminders about the mail:

First-class mail is delivered 2-5 days after it is received by the US Postal Service.

Voters should submit their ballot request as soon as possible, but at least 15 days before Election Day.

Voters should mail their completed ballots as soon as possible, but no later than a week before Election Day.

Network’s Missing Voter Project is powering a people’s movement, one voter at a time

The Missing Voter Project was launched in 2004 to reach and mobilize new and infrequent voters in South Carolina.

Unlike other voter registration drives, the MVP is nonpartisan, ongoing, and focused on historically under-represented communities.

It was created by the SC Progressive Network to grow an informed electorate with the power to mobilize around public policies critical to young people, working families, and communities of color in South Carolina.

While most voter registration drives start anew each election cycle, the MVP works year-round to inform citizens about local and county matters that impact their lives, and to invite them to become involved in a growing movement for social and political change.

This year, the MVP is using a novel peer-driven approach of asking young, Black voters to reach young, Black non-voters and get them to the polls in November.

Just 15% of South Carolina’s Black voters under age 26 went to the polls in the last general election. Those voters are central to our 2020 MVP campaign.

Over the summer, MVP organizers targeted Saluda and Fairfield, taking advantage of the relationships the Network has built in those counties over the 26 years it has been organizing.

This year, we are raising funds to recruit county-based MVP teams from the 23,087 young Black South Carolinians who voted in the last general election. We challenged them to be the catalyst to turn out record numbers of young, Black voters in 2020. They have the numbers to change history.

Whether or not the MVP succeeds in that goal this year, we will have laid the groundwork for a multi-year plan to level the imbalance of power codified in the state’s current constitution, created in 1895 specifically to disenfranchise its African-American citizens.

A reckoning is upon us.

These are perilous times, to be sure, but they offer an unprecedented opportunity to challenge, and begin to dismantle, South Carolina’s racially segregated politics.

What we do between now and the election on Nov. 3 can change our lives for many years to come.

While 78% of South Carolina’s nonwhite voting-age population is registered, only half of them regularly vote. An average of 500,000 of the state’s one million registered Blacks (along with 100,000 unregistered citizens), are sitting out the elections. If those “missing voters” were mobilized, it could change everything.

The continuing racial disparities in jobs, housing, health care, poverty, education, and the criminal justice system show that Black lives are devalued in South Carolina. It is not an accident, and it is a problem that won’t fix itself.

Reality check: for decades, incumbent legislators have been allowed to carve political maps to retain their power by packing Black and White voters into racially segregated political districts. This creates safe seats for incumbents but dilutes the effectiveness of Black votes on state policies.

The MVP is working to motivate and sustain Black civic engagement by showing that we can increase the turnout of Black voters by 200,000 in the only political district that cannot be gerrymandered: a statewide race.

The average margin of victory in the last three governor’s races was only 125,877 votes. If our plan works, it would prove to the half-million Black registered nonvoters that if political districts were not racially segregated their vote could change public policy.

By 2022, an energized Black electorate in South Carolina could determine the state’s next governor, attorney general, and superintendent of education.

The 2020 MVP training will prepare activists to organize county-based petitions in 2021 to force a constitutional amendment on the 2022 ballot to end race-based redistricting. It is part of the Network’s Fair Maps campaign to end partisan gerrymandering in South Carolina. See FairMapsSC.com for details.

This year’s MVP campaign is designed to train and sustain county-based teams of activists who understand that to make meaningful change will take commitment and longterm vision.

Training includes a component to involve MVP organizers in the statewide election protection work that the Network has anchored since 2004, when the nation’s first paperless voting system was implemented.

MVP volunteers will meet their county’s election director, become credentialed poll watchers, and have the opportunity to participate in their county’s vote certification process.

Volunteer organizers will be trained to help with Census enumeration. With only 57% of citizens counted, South Carolina ranks 44th among states. Each uncounted resident costs our cash-strapped state $15,000 in federal funds this decade.

Last year, we partnered with the new leadership of the NAACP State Conference to test the 2020 MVP to see whether it could effectively be launched statewide. The Memorandum of Understanding was enthusiastically endorsed by the national NAACP office. The plan set our two-county model in place.

As the pandemic worsened, we adjusted recruiting, training, and mobilization strategies to keep organizers and the public safe.

We mailed a letter to young Black voters in our two targeted counties — Saluda and Fairfield — inviting them to join their county MVP team.

It took until 2018 for majority-Black Fairfield County to elect its first Black state representative since Reconstruction.

Ten years earlier, the MVP conducted its first student training at the only high school in Fairfield County. The team registered three times as many new voters than had previously voted. At almost 25%, the county now has the state’s second-highest youth participation rate.

Saluda County is majority-White, and had just 65 young, Black voters in 2018. For decades, the Network has worked with the Riverside CDC, the only enduring civic engagement organization in the county. It prepared us for this campaign.

The level of capacity in this rural county with poor broadband service is requiring a different organizing model than in Fairfield. The differences between the two inform how we are conducting MVP outreach in other counties.

In Saluda and Fairfield counties, the NAACP Branch has partnered with local Network members to support the MVP teams. With their help, we are soliciting community buy-in to help sustain core teams of local activists beyond 2020. We are paying a stipend to trained organizers. The more money we raise, the more boots we can put on the ground.

In both counties, a vibrant organizing core is taking root. Word is getting out that something is happening.

Each week, MVP volunteers are being trained through Zoom sessions, supplemented with socially distanced and masked in-person meetings.

Training includes a short course on democracy and a brief but critical history lesson that explains how our democracy was made — and how we can remake it to be more equitable for a new generation.

The young organizers are excited about leading such a bold and hopeful plan. They are making their first round of calls to other young voters in their county using the State Voices database and an automated Virtual Phone Bank that trained volunteers can access from their phones.

When that list is finished, they will begin calling the registered voters their age who didn’t vote. The next round of calls will go to unregistered young people. And when they have contacted and cajoled their peers, they will then begin calling the county’s older citizens.

With organizing underway in the model counties, the MVP is focusing on Richland County, which houses the state Capitol as well as two HBCUs.

Just 4,306 out of 27,397 young, Black residents of Richland County voted in 2018.

We can change that. 2020 offers an unprecedented opportunity to reconsider our shared values and transform the institutions that have failed in South Carolina by creating systems that work for everyone, not the select few.

There are no short cuts when it comes to grassroots organizing. Trust takes time. Our years of developing ties in some of the state’s most neglected counties has laid the groundwork for us to take the MVP into communities where we can make the biggest impact — not just in the next election, but for decades to come.

While 78% of South Carolina’s nonwhite voting-age population is registered, only half of them regularly vote. An average of 500,000 of the state’s one million registered Blacks (along with 100,000 unregistered citizens), are sitting out the elections. If those “missing voters” were mobilized, it could change everything.

The continuing racial disparities in jobs, housing, health care, poverty, education, and the criminal justice system show that Black lives are devalued in South Carolina. It is not an accident, and it is a problem that won’t fix itself.

Reality check: for decades, incumbent legislators have been allowed to carve political maps to retain their power by packing Black and White voters into racially segregated political districts. This creates safe seats for incumbents but dilutes the effectiveness of Black votes on state policies.

The MVP is working to motivate and sustain Black civic engagement by showing that we can increase the turnout of Black voters by 200,000 in the only political district that cannot be gerrymandered: a statewide race.

The average margin of victory in the last three governor’s races was only 125,877 votes. If our plan works, it would prove to the half-million Black registered nonvoters that if political districts were not racially segregated their vote could change public policy.

By 2022, an energized Black electorate in South Carolina could determine the state’s next governor, attorney general, and superintendent of education.

The 2020 MVP training will prepare activists to organize county-based petitions in 2021 to force a constitutional amendment on the 2022 ballot to end race-based redistricting. It is part of the Network’s Fair Maps campaign to end partisan gerrymandering in South Carolina. See FairMapsSC.com for details.

This year’s MVP campaign is designed to train and sustain county-based teams of activists who understand that to make meaningful change will take commitment and longterm vision.

Training includes a component to involve MVP organizers in the statewide election protection work that the Network has anchored since 2004, when the nation’s first paperless voting system was implemented. MVP volunteers will meet their county’s election director, become credentialed poll watchers, and have the opportunity to participate in their county’s vote certification process.

Volunteer organizers will be trained to help with Census enumeration. With only 57% of citizens counted, South Carolina ranks 44th among states. Each uncounted resident costs our cash-strapped state $15,000 in federal funds this decade.

Last year, we partnered with the new leadership of the NAACP State Conference to test the 2020 MVP to see whether it could effectively be launched statewide. The Memorandum of Understanding was enthusiastically endorsed by the national NAACP office. The plan set our two-county model in place.

As the pandemic worsened, we adjusted recruiting, training, and mobilization strategies to keep organizers and the public safe.

We mailed a letter to young Black voters in our two targeted counties — Saluda and Fairfield — inviting them to join their county MVP team.

It wasn’t until 2018 that majority-Black Fairfield County elected its first Black state representative since Reconstruction.

Ten years earlier, the MVP conducted its first student training at the only high school in Fairfield County. The team registered three times as many new voters than had previously voted. At almost 25%, the county now has the state’s second-highest youth participation rate.

Saluda County is majority-White, and had just 65 young, Black voters in 2018. For decades, the Network has worked with the Riverside CDC, the only enduring civic engagement organization in the county. It prepared us for this campaign.

The level of capacity in this rural county with poor broadband service is requiring a different organizing model than in Fairfield. The differences between the two inform how we are conducting MVP outreach in other counties.

In Saluda and Fairfield counties, the NAACP Branch has partnered with local Network members to support the MVP teams. With their help, we are soliciting community buy-in to help sustain core teams of local activists beyond 2020. We are paying a stipend to trained organizers. The more money we raise, the more boots we can put on the ground.

In both counties, a vibrant organizing core is taking root. Word is getting out that something is happening.

Each week, MVP volunteers are being trained through Zoom sessions, supplemented with socially distanced and masked in-person meetings.

Training includes a short course on democracy and a brief but critical history lesson that explains how our democracy was made — and how we can remake it to be more equitable for a new generation.

The young organizers are excited about leading such a bold and hopeful plan. They are making their calls to other young voters in their county using the State Voices database and an automated Virtual Phone Bank that trained volunteers can access from their phones. When that list is finished, they will begin calling the registered voters their age who didn’t vote. The next round of calls will go to unregistered young people. And when they have contacted and cajoled their peers, they will then begin calling the county’s older citizens.

With organizing underway in the model counties, the MVP is focusing on Richland County, which houses the state capitol as well as two HBCUs.

Just 4,306 out of 27,397 young, Black residents of Richland County voted in 2018.

We can change that. 2020 offers an unprecedented opportunity to reconsider our shared values and transform the institutions that have failed in South Carolina by creating systems that work for everyone, not the select few.

There are no short cuts when it comes to grassroots organizing. Trust takes time. Our years of developing ties in some of the state’s most neglected counties has laid the groundwork for us to take the MVP into communities where we can make the biggest impact — not just in the next election, but for decades to come.

Please VOLUNTEER or DONATE!

MissingVoterProject.com

• • •

SC’s response to COVID crisis exposes liability of letting corporate interests dictate public policy

The spike in COVID cases in South Carolina is a stark example of the state’s habit of putting profits above public health. The policies now being implemented in South Carolina by the governor and by the Department of Health and Environmental Control were designed by the fast food industry, the hospitality industry, and the other corporations that make their money on wage workers and service industries. The accelerateSC task force was designed to put South Carolina back to work — without worker input.

The Network and allies sent a letter to the DHEC board on July 8 imploring the agency to step up and do what the law instructs the it to do. Meanwhile, we are taking testimony from workers put at risk by the failure of leadership to protect them on the job. Call 803-601-8000 for details.

Network and allies press DHEC to take mandatory measures on COVID guidelines for workers

Workers invited to provide legal testimony

Organizations representing scores of thousands of members across the state sent a letter today to the Board of the SC Dept. of Health and Environmental Control citing DHEC’s authority, and responsibility, to issue and enforce mandatory compliance with the agency’s COVID-19 safety measures. The organizations represent the public at risk, as well as the workers and their families who are being required to work or face being fired for following Gov. Henry McMaster and DHEC’s advice to follow CDC guidelines during the pandemic.

“It is clear that urging citizens and employers to mask up and follow safety guidelines isn’t working,” said Rep. Gilda Cobb-Hunter, Executive Director of CASA Family Systems, an Orangeburg-based shelter for battered women and children. “The virus has become a political issue, and DHEC must stand up for science or we are all going to continue to suffer,” Cobb-Hunter said.

“It is clear that urging citizens and employers to mask up and follow safety guidelines isn’t working,” said Rep. Gilda Cobb-Hunter, Executive Director of CASA Family Systems, an Orangeburg-based shelter for battered women and children. “The virus has become a political issue, and DHEC must stand up for science or we are all going to continue to suffer,” Cobb-Hunter said.

SC NAACP President Brenda Murphy stressed the disproportionate impact of the virus on working people of color. “Those most vulnerable to the disease are the least protected workers,” Murphy said. “They fear getting fired if they challenge unsafe conditions at work.”

The letter to the DHEC Board points out that the governor’s Executive Order declaring a State of Emergency ordered DHEC to “utilize any and all necessary and appropriate emergency powers, as set forth in the Emergency Health Powers Act (Title 44, Chapter 4 of the SC Code of Laws) that regulates your agency: During a state of public health emergency, DHEC must use every available means to prevent the transmission of infectious disease and to ensure that all cases of infectious disease are subject to proper control and treatment.”

SC AFL-CIO Charles Brave Jr. said, “The governor wants to sound like he has no enforceable authority to require that COVID guidelines be followed, but we know that’s not true. His priority of keeping corporate profits up and workers’ rights down is killing people.”

The Charleston Alliance for Fair Employment (CAFE) fights for wage workers in the hospitality and service industries. “Our members don’t have sick leave, and will get fired if they don’t show up for work,” said CAFE President Kerry Taylor. “Many of them are single mothers who are forced to work sick or lose their income if they have to stay home with a sick child.”

“The pandemic underscores how cruel public policies are in South Carolina,” said Brett Bursey, Executive Director of the SC Progressive Network‘s 24-year-old nonpartisan policy institute. The state has a long history of sacrificing workers’ health for corporate profit.”

The Network fought legislation introduced in 2013 to prohibit local governments from establishing sick leave policies to prevent sick workers from spreading diseases. In 2017, Gov. McMaster signed the anti-sick leave legislation into law.

The bill was promoted by the same hospitality corporations that comprised the governor’s accelerateSC task force that contributed over $21,000 to his current campaign account. Members of the House Ways and Means Committee, which passed the Hospitality Task Force’s $2 billion COVID relief budget last month, received over $100,000 in campaign contributions from the same hospitality industry that relies on low-wage service workers with no sick leave. They did this without a public hearing.

Workers and their families threatened by the state’s failure to adequately address the continuing spread of the virus and their potential loss of employment are encouraged to contact the Network at 803-808-3384 or email network@scpronet.com. Fast food workers should address their concerns to CAFE at kerryt33@gmail.com. Workers testimony is needed to develop a legal case seeking to compel state agencies compliance with existing statutes regulating health emergencies.