On the evening of Saturday, Jan. 25, friends, allies, and alumni will gather at the historic Big Apple in the heart of Columbia to celebrate 10 years of teaching truth in South Carolina.

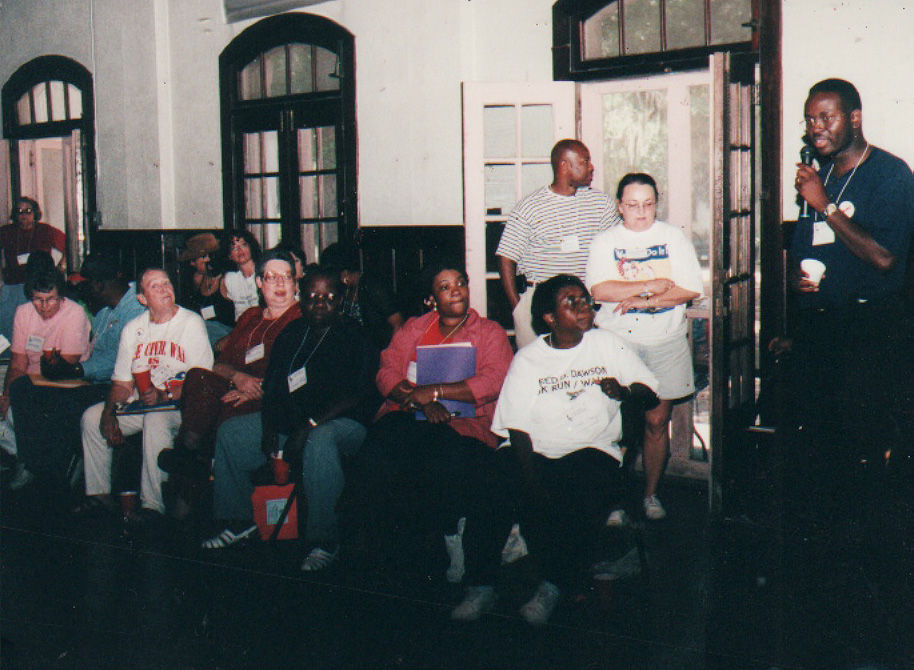

The SC Progressive Network started the school in 2015 to teach civics, organizing skills and strategies, and a true people’s history of the Palmetto State. Since then, some 400 students of all ages, backgrounds, and interests have graduated from the intensive four-month program. Hundreds more have attended the school’s public programs that are offered free on most Sundays during the session.

The evening will be a chance to celebrate the school and the people who have made it a first-class, graduate-level experience that is unlike anything else in South Carolina. In fact, other states are looking to the school as a model to help address the education crisis in this country.

Network Executive Director Brett Bursey said, “Of all the work we’ve done, the school is the most rewarding and necessary. It is exceeding our expectations, and we are gratified by the buy-in we are getting from those who understand the value of education and speaking truth to power.” (You can watch him doing the latter in this clip from a 2022 education subcommittee hearing on Critical Race Theory.)

“The Modjeska Simkins School has worked hard for 10 years to teach the true history of our state,” said Dr. Robert Greene II, who has served as lead instructor of the Modjeska Simkins School since 2019. “Our upcoming gala will showcase the best of our state, through our students and guest faculty. South Carolina’s history provides a template to fight against oppression and for freedom. Let’s continue this great work together!”

The gala will feature renowned poet Nikky Finney, a longtime supporter of the school and the Network. She spoke at the rally the Network organized in 2017, and she addressed the Modjeska School graduates in 2021. She is a powerful speaker and writer.

The evening will include live jazz and a dance demonstration by Richard Durlach, who owns the Big Apple where the dance craze was born in 1937. We encourage attendees to wear 1930s-era dance attire — or at least a festive hat.

Proceeds will help us continue to teach South Carolina’s real history in a time of book bans and shrinking history programs across the state. If you cannot attend, consider making tickets a gift for a friend. Or you can make a general donation HERE of any amount. Every dollar is appreciated, and allows us to offer student scholarships and to cover travel costs of guests speakers.

We are very proud of the school, and are busy planning programs to expand our reach across the state. This event will not just be a wonderful evening, it will boost our visibility ahead of the spring session, which runs March 1 through June 28. Students may attend online or in-person at our HQ in Columbia, located at 1340 Elmwood Ave.

Find out more about the Big Apple in this 2019 piece in Oxford American by Dr. Greene II.

See our photo album HERE.

Questions? Call 803-808-3384 or email network@scpronet.com.