Category Archives: Network News/Events

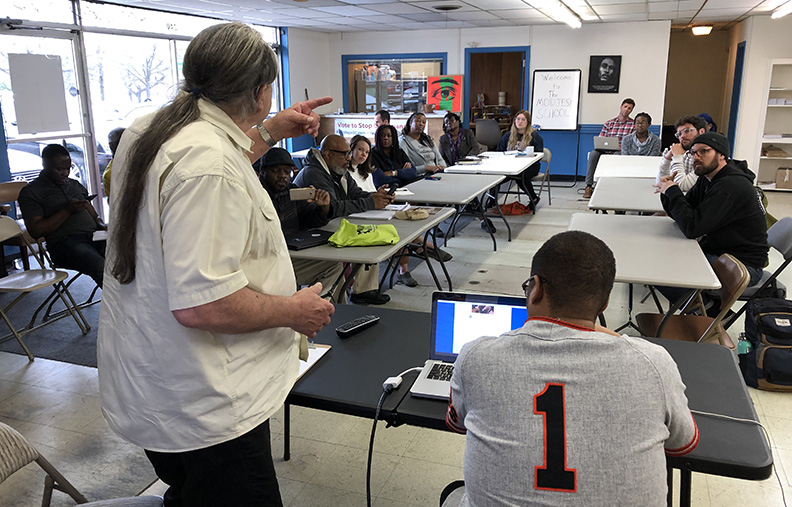

Young organizers find allies and a meeting space at GROW

After canvassing in Orangeburg on Saturday, young activists from the Union of Southern Service Workers debriefed at GROW. Good crowd. Great energy.

Noted historians, writers, lawyers, and community activists set to teach spring session of Modjeska Simkins School

We are gearing up for the spring semester of the Modjeska Simkins School, now in its ninth year, and are so pleased with the quality of appicants to date. Deadline to apply is Feb. 28, with orientation on March 5. Classes are held Monday evenings 6:30 – 8:30 March 6 through June 26 in-person at GROW, 1340 Elmwood Ave., and on Zoom.

This course is led by academics and authors, and seasoned community activists. Additional Sunday programs that are optional for students and open to the public may be added as the semester progresses.

• • •

Dr. Robert Greene II, who teaches history at Claflin University, has served as the Modjeska Simkins School’s lead instructor since 2019. Dr. Greene is book reviews editor and blogger for the Society of U.S. Intellectual Historians. Along with Tyler D. Parry, he is the co-editor of Invisible No More: The African American Experience at the University of South Carolina. He is working on a book examining the role of Southern African Americans in the Democratic Party from 1964 through the 1990s. He has published several articles and book chapters on the intersection of memory, politics, and African American history, and has written for numerous popular publications, including The Nation, Oxford American, Dissent, Scalawag, Jacobin, In These Times, Politico, and The Washington Post.

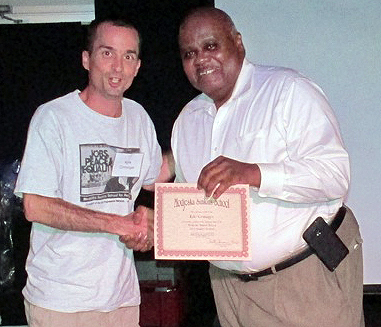

Brett Bursey, executive director of the SC Progressive Network, is a founder of the Modjeska Simkins School. He worked closely with Modjeska Simkins during the last 18 years of her busy life, and has been a full-time social justice organizer for more than 50 years in South Carolina.

Guest speakers for 2023

Dr. Catherine Adams presents on “The Resistance, Rebellions and Repression of Natives and the Enslaved.” Dr. Adams is an Associate Professor at Claflin University and holds a Ph.D. in Afro-American Studies from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her recent research focuses on Maroonage.

Dr. Millicent Brown, a Senior Research Fellow at Claflin University, will share her experience as the first child to integrate Charleston public schools in 1963. She remains engaged in advocating for education equality.

Dr. Vernon Burton’s book Lincoln’s Unfinished Work is a “thought-provoking exploration of the unfinished work of democracy, particularly as it pertains to the legacy of slavery and white supremacy in America” by LSU Press. Dr. Burton is a Distinguished Professor of History at Clemson University is a prolific author and scholar. His earlier title, The Age of Lincoln, was selected for Book of the Month Club, History Book Club and Military Book Club and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Dr. Burton is nationally respected as a foremost scholar on Lincoln and Ben Tillman.

Cecil Cahoon is a board member of the SC Progressive Network and a regional organizer for the National Education Association.

Dr. John Crangle teaches history and is a licensed SC attorney. He was involved in Operation Lost Trust in the 1990s, which lead to the revision of the State Ethics Act. Since 1990, Dr. Crangle has been a watchdog for state and local government. He is currently the lead plaintiff in a case against the state attorney general over the award of $75 million in attorney fees from the federal settlement relating to the Savannah River Nuclear site.

Armand Derfner, a graduate of Princeton University and Yale Law School, has been a civil rights lawyer for more than a half century. As part of that work, he helped shape the Voting Rights Act in a series of major Supreme Court cases and in work with Congress to help draft voting rights and other civil rights laws. He is currently Distinguished Scholar in Constitutional Law at the Charleston School of Law. Derfner recently co-authored Justice Deferred with Vernon Burton, which documents racist rulings of the US Supreme Court.

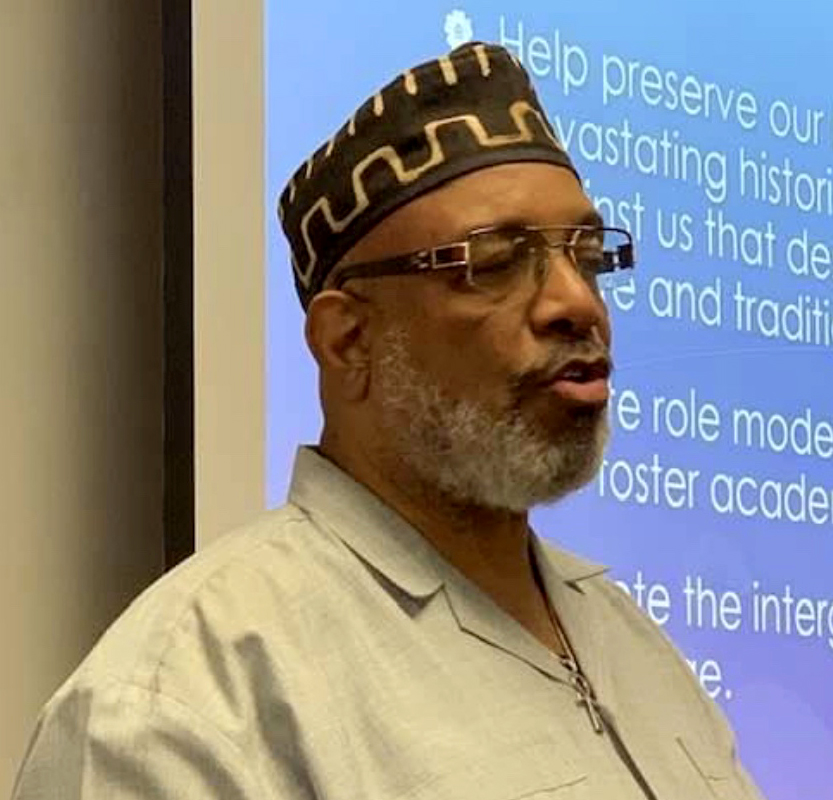

Dr. Bobby Donaldson leads the Center for Civil Rights History and Research, housed in the Hollings Special Collections Library. He also serves as the lead scholar for Columbia SC 63: Our Story Matters, a documentary history initiative that chronicles the struggle for civil rights and social justice in Columbia. A team from the Center will present on the modern Civil Rights history of South Carolina.

Dr. Justene Edwards, an associate professor of history at the University of Virginia is a specialist in American Slavery and the History of American Capitalism. She will discuss her recent research and book, Unfree Markets: The Slaves’ Economy and the Rise of Capitalism in South Carolina. Dr. Edwards’ research reveals the development of market capitalism by South Carolina’s colonial slave masters as a means of controlling both the market and the enslaved.

Bill Fletcher Jr. has been active in workplace and community struggles as well as electoral campaigns. He has worked for several labor unions in addition to serving as a senior staffperson in the national AFL-CIO. Fletcher is the former president of TransAfrica Forum; a Senior Scholar with the Institute for Policy Studies; and in the leadership of several other projects. Fletcher is co-author (with Peter Agard) of The Indispensable Ally: Black Workers and the Formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, 1934-1941; co-author (with Dr. Fernando Gapasin) of Solidarity Divided: The crisis in organized labor and a new path toward social justice; and author of They’re Bankrupting Us – And Twenty other myths about unions. Fletcher is a syndicated columnist and a regular media commentator on television, radio and online.

Dr. Burnette Gallman, a Columbia physician and member of the Modjeska Simkins School’s Board of Directors, shares the highlights of African history before the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. He has been hosting seminars on African history for 40 years, and serves on the National Board of the Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations.

Dr. Erik Gellman, an Associate Professor of History at UNC Chapel Hill, wrote Death Blow to Jim Crow in 2012, the first book about the Southern Negro Youth Congress. Dr. Gellman will focus on why the largest most diverse, and FBI infiltrated human rights conference ever held in the segregated South, was held in Columbia SC in 1946.

Chris Judge, Assistant Director Native American Studies Center USC Lancaster unpacks the loss of land, life and culture of native people. He is an anthropological archaeologist, and for more than 30 years has been studying Native Americans in South Carolina.

Dr. Ed. Madden, who recently served as poet laureate for the City of Columbia, has been a leading organizer for LGBTQ rights, including the successful marriage equality campaign in South Carolina. He is a professor of English, with a focus on Irish literature, at the University of South Carolina. There, he is also director of the women’s and gender studies program. His academic areas of specialization include Irish culture; British and Irish poetry; LGBTQ literature, sexuality studies, and history of sexuality; and creative writing and poetry. In 2019 he was named a Poet Laureate Fellow of the Academy of American Poets and a visiting artist fellow at the Instituto Sacatar in Bahia, Brazil. In 2015, Madden was named Columbia’s first poet laureate, a post he maintains today. Madden has been a South Carolina Academy of Authors Fellow in poetry twice and was South Carolina Arts Commission Prose Fellow in 2011. He has been writer-in-residence at the Riverbanks Botanical Garden and at Fort Moultrie in Charleston as part of the state’s African American Heritage Corridor project. He also was 2006 artist-in-residence for South Carolina State Parks. His numerous publishing and editing credits include four of his own: Nest, Ark, Prodigal: Variations, and Signals, and his chapbook So They Can Sing won the 2016 Robin Becker Chapbook Prize.

Kamau Marcharia is a longtime South Carolina social justice activist and former council member from Fairfield County. Marcharia was arrested at age 16, and served 11 years of a 50-year sentence for a crime he did not commit.

Lewis Pitts takes us through the long and frightening evolution of corporations becoming people. Pitts grew up in SC and spent 40 years as an attorney for the people before resigning from the legal profession in disgust. He is a founding member of the Project on Corporations Law and Democracy (POCLAD) and is a Modjeska Simkins School graduate.

Rob Richie has led FairVote, a nonpartisan organization committed to practical voting reforms to make democracy more functional and representative, since its founding in 1992. He is a frequent national media source and the author of 11 books on voting reforms.

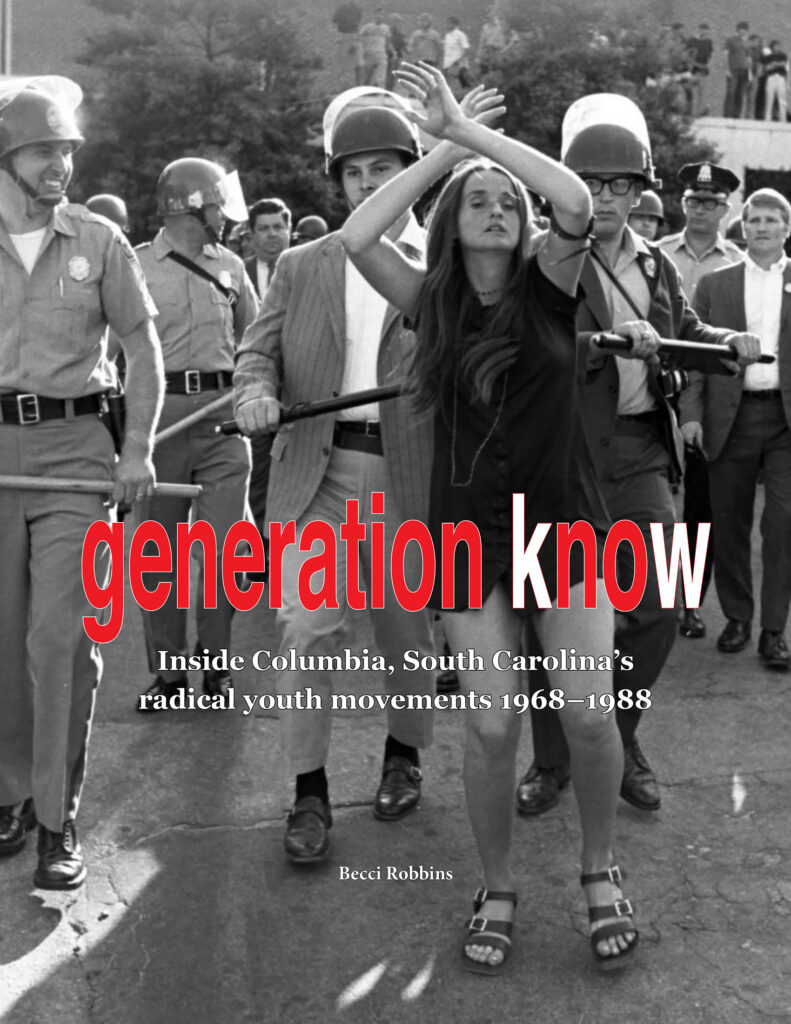

Becci Robbins has served as communication director for the SC Progressive Network since its founding in 1996. She was editor of POINT, an alternative South Carolina newspaper, from 1991 until 2000. She has written five short books on South Carolina’s lesser-known heroes and history. Her latest work is Generation Know: Inside Columbia, South Carolina’s, radical youth movements.

Dr. Jennifer Taylor, Assistant Professor of Public History at Duquesne University. Dr. Taylor earned her Ph.D. at USC and specializes in the tensions involved in public history commemorations and interpretation. Her recent scholarship explores the ways in which Reconstruction history has been contested and commemorated in South Carolina, including how museums can help the public understand white supremacy and the similarities between racist militia movements of the Reconstruction era and today’s insurrectionists.

Dr. Kerry Taylor, a professor of Labor History at the Citadel, will discuss the state of organized labor in South Carolina. Dr. Taylor is also a longtime activist for workers’ rights in Charleston.

Enrollment now open for Modjeska Simkins School’s spring session

The Modjeska Simkins School of Human Rights is now accepting applications to its spring 2023 session. Classes will be held Monday evenings March 5 through June 26 online and at the SC Progressive Network’s newly renovated HQ at 1340 Elmwood Ave. in Columbia, next to Simkins’ historic home.

Launched in 2015 and named after the famed South Carolina human rights advocate Modjeska Monteith Simkins, the school teaches the true and uncensored history of South Carolina, and provides tools for effective citizenship.

Claflin University assistant professor Dr. Robert Greene II has served as the Modjeska School’s lead instructor since 2019. “The school continues a long and storied tradition of linking civics, political action, and life-long learning,” Greene said. “Such a history does emphasize the nature of oppression in the Palmetto State’s history, but the school equally teaches the spirit of justice, freedom, and equality that so many in South Carolina have fought for through the centuries. In an age like ours where teaching true history is under attack, the Modjeska Simkins School represents a different path for teaching and learning history.”

Dr. Greene has published more than 350 articles in publications ranging from the Washington Post to The Nation. Most recently, he co-edited the book Invisible No More documenting the experiences of African Americans at USC.

“Dr. Greene has a wealth of knowledge, but he also has a rare talent for teaching,” said Brett Bursey, executive director of the SC Progressive Network Education Fund, the school’s sponsor. “Robert teaches a living history that connects the past with our present, which is critical to truly understanding current reality and to any hope of making meaningful change for the collective good.”

Bursey has arranged an impressive line-up of guest teachers this session, maximizing connections he has cultivated with activists, authors, and historians over his 50 years as a South Carolina community organizer. The roster of presenters makes the school a unique experience, one that students cannot get anywhere else.

Dr. Burnette Gallman, who teaches African history,took the course twice, and is a presenter this session. He said, “As the lies and the assault on truth continue, the Modjeska School is a breath of fresh air. It provides a correction of the lies that have been told in schools for generations, as well as a firewall against the lies being legislated today. Everyone should take this course.”

The school has attracted a mix of students of all ages, backgrounds, and professional experiences. April Lott, president of the Charleston Central Labor Council, vice-president of the SC AFL-CIO, and president of AFGE, the regional union for Social Security employees, attended last year’s session. “The school opened my eyes to my own history here in South Carolina,” she said. “As a Charleston native, there was so much rich history that I did not know — the good, the bad, and the bitter ugly. As a union leader and labor activist, learning these things through the life of Ms. Modjeska not only inspired me but it gave me validation that I can fight for the working families of SC. I learned that I will have battles and disappointments but if I stay strong and hold to my faith, I will endure. I stand on the shoulders of Ms. Modjeska, and am proud graduate of the Modjeska Simkins School.”

Cecil Cahoon, an education expert and a Modjeska School graduate, said the school presents the essential foundation for informed citizenship in South Carolina. “Its content is heavy on documentary evidence of its peoples’ real history, not the sanitized narratives approved by its ruling class and textbook adopters for generations. Here, students are introduced to consequential persons and events that have long been obscured by white supremacist doctrine but nevertheless shaped today’s South Carolina. Graduates leave with a better understanding of the state’s present conditions and challenges, and of how informed citizenship can address systemic injustices to improve its future.”

Cahoon said, “Only where truth is prized and shared, can there be liberty and justice for all. The Modjeska School is the modern representation of everything that South Carolina’s evolving aristocracy has ever feared and worked to prevent: truth being taught to its citizens.”

For details about the school or to apply to the 2023 session, see modjeskaschool.com.

Tuition for the spring session is $375. Payments may be made installments, and some scholarship assistance is available.

To apply, click HERE.

Tax deductible donations are always welcome to help provide student scholarships and stipends for guest teachers.

Questions? Call the Network’s office at 803-808-3384 or email network@scpronet.com.

Who was Lee Atwater? Watch the doc at GROW Movie Night Jan. 17

Join us Tuesday at 7pm for a free screening of Boogie Man, the documentary about SC native Lee Atwater, the bad boy of politics who wrote the GOP handbook for playing dirty. All are welcome at GROW, 1340 Elmwood Ave., in Columbia.

Watch trailer: HERE.

Listen to the explosive 1981 audio recording of Atwater talking about the Southern Strategy at a link posted by The Nation.

Generation Know, the new book by Network Communications Director Becci Robbins, includes a passage about Atwater and his role in shaping the modern Republican Party.

GROW-Book-excerptHonoring the radical Dr. King

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1967 speech at Riverside Church — a year to the day before his assassination — called for a “radical revolution of values.” At the Network and the Modjeska Simkins School, we are working to manifest his vision.

Dr. King said, “I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives, and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”“Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break the Silence,” considered King’s most controviersial speech, is worth revisiting.

This link takes you to an audio recording and a transcript.

Cheers to you!

With 2022 in the rearview, we wanted to take a moment to thank all of you who supported the Network this year by donating, volunteering, turning out, and keeping the faith in tough times.

Because of you, the Network was able to:

• complete renovation of our HQ, which is now fully wired and accessible, with a kitchen and a beer and wine license;

• monitor voting in all 46 counties during South Carolina’s midterm elections;

• complete the 7th annual session of the Modjeska Simkins School, graduating 29 students;

• surpass a GoFundMe goal to cover the cost of replacing the front window of our building after it was vandalized; and

• keep our quarterly commitment to clean our neighborhood through the city’s Adopt-a-Street program.

We are thrilled to see our newly renovated GROW building come to life with in-person meetings, classes, and events. After being separated during the pandemic, it has been wonderful to reconnect with old allies and new friends in a space that is all our own.

In September we held our first gathering, to launch the book Generation Know: Inside Columbia, South Carolina’s Radical Youth Movements 1968–1988. It is the fifth booklet we have published through grants from the Richland County Conservation Commission. We appreciate their continued support of our work to lift up the state’s lesser-known heroes and histories. You can order a copy here. Proceeds benefit the Modjeska School. Earlier books are free, and available at our office and online.

In September and October, we held a series of sessions to train volunteers to help with our election protection work, which the Network has spearheaded in South Carolina since 2008. During early voting and on Election Day, our volunteers circulated the 866-OUR-VOTE hotline number and monitored the polls. We have been invited to share our audit results and suggestions with the Legislative Audit Council, which was ordered to audit the 2022 election because of a proviso the uber-conservative Freedom Caucus slipped into the budget.

On Halloween, we resurrected the GROW tradition of throwing a Mutant Be-In. A ghastly time was had by all.

In November, GROW held its first jazz night, featuring the band Just Us. It has been filling the house on Monday nights ever since. The schedule will change in the new year to the first and third Thursdays, with an earlier start time of 7pm. No cover. Free snacks; beverages available for purchase.

On Dec. 5, we toasted the memory of Modjeska Simkins on her 123rd birthday. On the 16th we screened the recently restored documentary The Wobblies about the radical IWW union. Sara Williams and Arnold Karr opened and closed the evening with a few tunes from the Little Red Songbook. Our next Movie Night is on Jan. 17 at 7pm. We’ll watch Boogie Man, about SC political bad boy Lee Atwater.

In 2023, we will focus our attention on the Modjeska School, expanding its curriculum to include short courses, sessions for younger students, and programs for the public. Thanks to the school’s lead instructor, Dr. Robert Greene, and an impressive roster of guest speakers, the school continues to surpass our greatest expectations. Its value only increases with the accelerating assault public education and the teaching of history in South Carolina.

Our next full session will begin in late February and run through June. Once dates have been finalized, we’ll send notice that the application process is open.

To support the school, donate here. Funds will go toward student scholarships and teacher stipends.

What’s next?

With the building renovation complete, we are turning our attention to the exterior. Plans include landscaping, putting up a new sign, building a patio on the Marion Street side, and creating a hardscape buffer along the front of the building for privacy and protection. Want to help? We welcome donations here.

As we usher in the new year, we want to thank our members and allies who have helped build this community over 26 years. We are grateful, too, for our executive committee and transition team – Cecil Cahoon, April Lott, Burnie Gallman, and Russell Bannan — who have been retooling the organization’s form and function to meet the needs of a new generation. We’ll be sending out a progress report in the new year.

Finally, much love and appreciation to:

Michael Gooding and Richard Sylvester for their work renovating the building; Shannon Herin and James Carpenter for keeping our finances straight; Norman Miles for always stepping up to do the thankless tasks; Chris Gardner for his IT support and volunteer service; and longtime staffer Daniel Deweese, who is in New York studying at the New School until June, and is missed at the office.

Stay tuned for details on our Thunder and Lightning Awards dinner in February and retreat at Penn Center the first weekend in April.

Best wishes for a happy new year!

Brett and Becci

SC Education 101

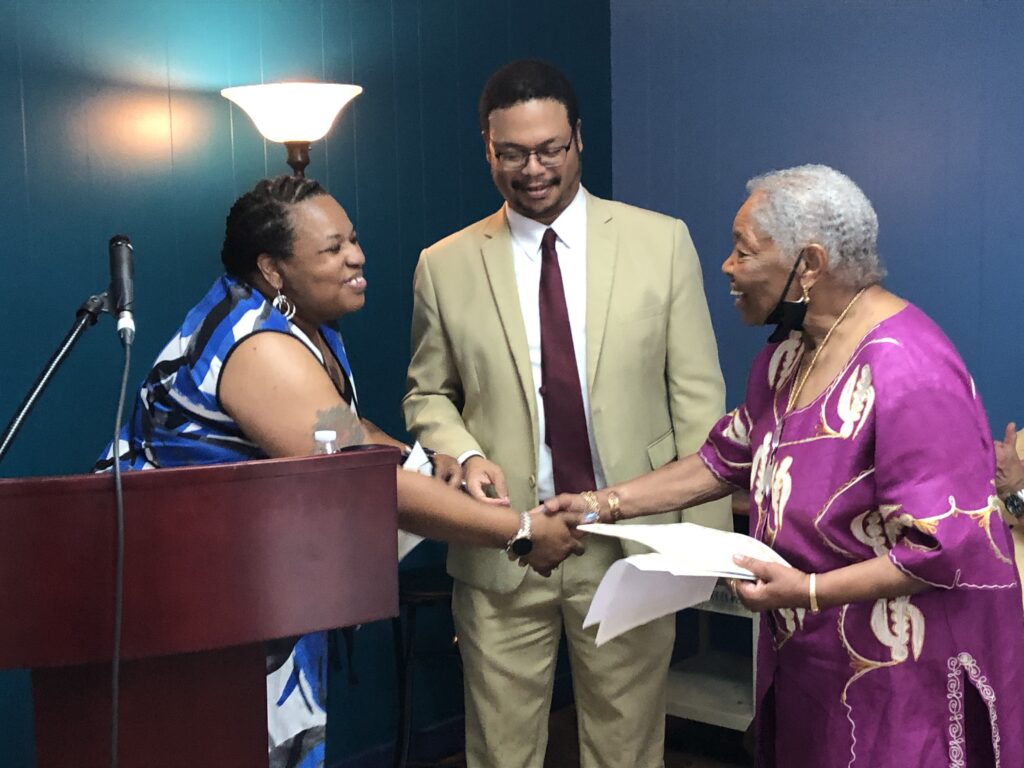

Remembering Modjeska Simkins on her birthday

On what would have been her 123rd birthday, friends and allies gathered to honor Modjeska Simkins in the SC Progressive Network‘s newly renovated HQ next door to the human rights icon’s historic home in Columbia.

People who knew her told stories about the woman they remember. People who wish they had known her, inclduing a few graduates of the Modjeska Simkins School, talked about what her legacy has meant to them. One can only imagine how proud she would be.

At evening’s end, everyone raised a glass of port for a toast. Cheers to the fighting spirit of Modjeska Monteith Simkins!

For more pictures and video clips, see our album.

All that jazz!

Mondays will never be the same at GROW, the Network’s HQ. We had our first Jazz Night on Nov. 14, a happening that will repeat every Monday at 8pm (unless it conflicts with a standing commitment the Network has, as is the case on Dec. 5, Modjeska Simkins’ birthday. That night, we will continue the tradition of celebrating our mentor with a toast and retelling of stories about her remarkable life. The drop-in starts at 5:30. All are welcome.)

Jazz Night was a soft launch for our newly renovated building, a chance to work out kinks before going public. It’s been great fun watching the place come to life with music, dancing, and fellowship. We hope you will stop by some coming Monday for a nightcap and swinging music. No cover charge.

Questions? Call 803-808-3384 or email network@scpronet.com.