Tag Archives: Fair Maps SC

Network’s Missing Voter Project is powering a people’s movement, one voter at a time

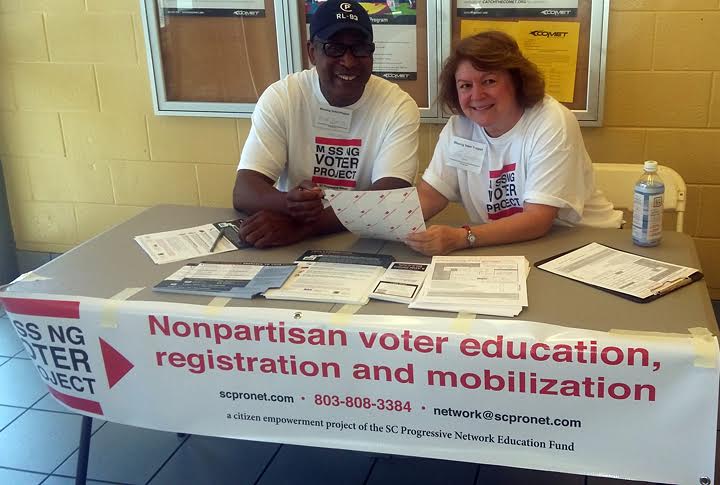

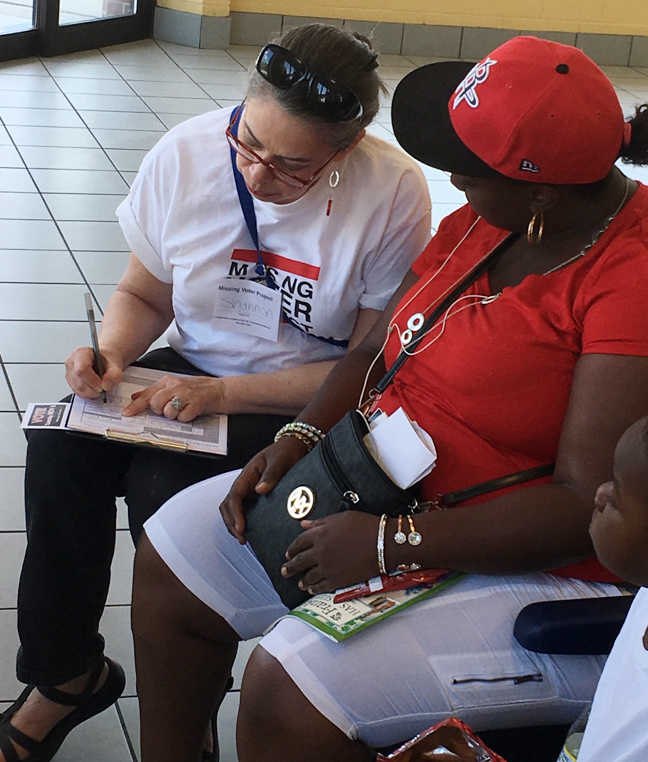

The Missing Voter Project was launched in 2004 to reach and mobilize new and infrequent voters in South Carolina.

Unlike other voter registration drives, the MVP is nonpartisan, ongoing, and focused on historically under-represented communities.

It was created by the SC Progressive Network to grow an informed electorate with the power to mobilize around public policies critical to young people, working families, and communities of color in South Carolina.

While most voter registration drives start anew each election cycle, the MVP works year-round to inform citizens about local and county matters that impact their lives, and to invite them to become involved in a growing movement for social and political change.

This year, the MVP is using a novel peer-driven approach of asking young, Black voters to reach young, Black non-voters and get them to the polls in November.

Just 15% of South Carolina’s Black voters under age 26 went to the polls in the last general election. Those voters are central to our 2020 MVP campaign.

Over the summer, MVP organizers targeted Saluda and Fairfield, taking advantage of the relationships the Network has built in those counties over the 26 years it has been organizing.

This year, we are raising funds to recruit county-based MVP teams from the 23,087 young Black South Carolinians who voted in the last general election. We challenged them to be the catalyst to turn out record numbers of young, Black voters in 2020. They have the numbers to change history.

Whether or not the MVP succeeds in that goal this year, we will have laid the groundwork for a multi-year plan to level the imbalance of power codified in the state’s current constitution, created in 1895 specifically to disenfranchise its African-American citizens.

A reckoning is upon us.

These are perilous times, to be sure, but they offer an unprecedented opportunity to challenge, and begin to dismantle, South Carolina’s racially segregated politics.

What we do between now and the election on Nov. 3 can change our lives for many years to come.

While 78% of South Carolina’s nonwhite voting-age population is registered, only half of them regularly vote. An average of 500,000 of the state’s one million registered Blacks (along with 100,000 unregistered citizens), are sitting out the elections. If those “missing voters” were mobilized, it could change everything.

The continuing racial disparities in jobs, housing, health care, poverty, education, and the criminal justice system show that Black lives are devalued in South Carolina. It is not an accident, and it is a problem that won’t fix itself.

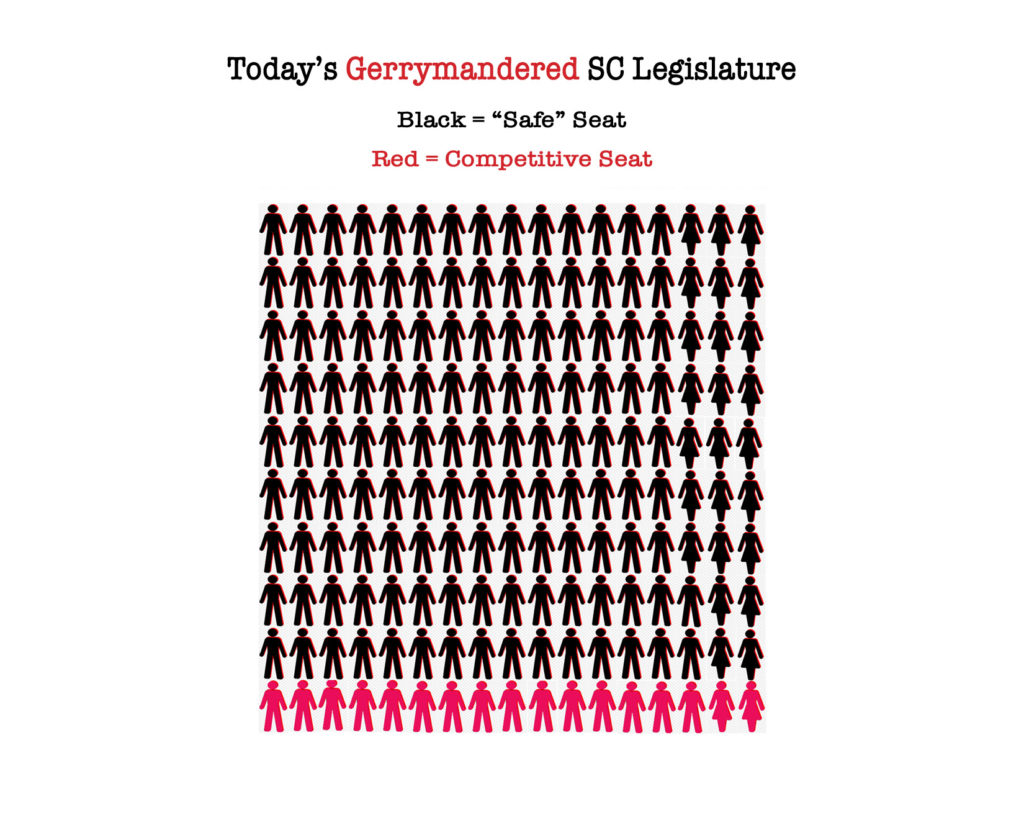

Reality check: for decades, incumbent legislators have been allowed to carve political maps to retain their power by packing Black and White voters into racially segregated political districts. This creates safe seats for incumbents but dilutes the effectiveness of Black votes on state policies.

The MVP is working to motivate and sustain Black civic engagement by showing that we can increase the turnout of Black voters by 200,000 in the only political district that cannot be gerrymandered: a statewide race.

The average margin of victory in the last three governor’s races was only 125,877 votes. If our plan works, it would prove to the half-million Black registered nonvoters that if political districts were not racially segregated their vote could change public policy.

By 2022, an energized Black electorate in South Carolina could determine the state’s next governor, attorney general, and superintendent of education.

The 2020 MVP training will prepare activists to organize county-based petitions in 2021 to force a constitutional amendment on the 2022 ballot to end race-based redistricting. It is part of the Network’s Fair Maps campaign to end partisan gerrymandering in South Carolina. See FairMapsSC.com for details.

This year’s MVP campaign is designed to train and sustain county-based teams of activists who understand that to make meaningful change will take commitment and longterm vision.

Training includes a component to involve MVP organizers in the statewide election protection work that the Network has anchored since 2004, when the nation’s first paperless voting system was implemented.

MVP volunteers will meet their county’s election director, become credentialed poll watchers, and have the opportunity to participate in their county’s vote certification process.

Volunteer organizers will be trained to help with Census enumeration. With only 57% of citizens counted, South Carolina ranks 44th among states. Each uncounted resident costs our cash-strapped state $15,000 in federal funds this decade.

Last year, we partnered with the new leadership of the NAACP State Conference to test the 2020 MVP to see whether it could effectively be launched statewide. The Memorandum of Understanding was enthusiastically endorsed by the national NAACP office. The plan set our two-county model in place.

As the pandemic worsened, we adjusted recruiting, training, and mobilization strategies to keep organizers and the public safe.

We mailed a letter to young Black voters in our two targeted counties — Saluda and Fairfield — inviting them to join their county MVP team.

It took until 2018 for majority-Black Fairfield County to elect its first Black state representative since Reconstruction.

Ten years earlier, the MVP conducted its first student training at the only high school in Fairfield County. The team registered three times as many new voters than had previously voted. At almost 25%, the county now has the state’s second-highest youth participation rate.

Saluda County is majority-White, and had just 65 young, Black voters in 2018. For decades, the Network has worked with the Riverside CDC, the only enduring civic engagement organization in the county. It prepared us for this campaign.

The level of capacity in this rural county with poor broadband service is requiring a different organizing model than in Fairfield. The differences between the two inform how we are conducting MVP outreach in other counties.

In Saluda and Fairfield counties, the NAACP Branch has partnered with local Network members to support the MVP teams. With their help, we are soliciting community buy-in to help sustain core teams of local activists beyond 2020. We are paying a stipend to trained organizers. The more money we raise, the more boots we can put on the ground.

In both counties, a vibrant organizing core is taking root. Word is getting out that something is happening.

Each week, MVP volunteers are being trained through Zoom sessions, supplemented with socially distanced and masked in-person meetings.

Training includes a short course on democracy and a brief but critical history lesson that explains how our democracy was made — and how we can remake it to be more equitable for a new generation.

The young organizers are excited about leading such a bold and hopeful plan. They are making their first round of calls to other young voters in their county using the State Voices database and an automated Virtual Phone Bank that trained volunteers can access from their phones.

When that list is finished, they will begin calling the registered voters their age who didn’t vote. The next round of calls will go to unregistered young people. And when they have contacted and cajoled their peers, they will then begin calling the county’s older citizens.

With organizing underway in the model counties, the MVP is focusing on Richland County, which houses the state Capitol as well as two HBCUs.

Just 4,306 out of 27,397 young, Black residents of Richland County voted in 2018.

We can change that. 2020 offers an unprecedented opportunity to reconsider our shared values and transform the institutions that have failed in South Carolina by creating systems that work for everyone, not the select few.

There are no short cuts when it comes to grassroots organizing. Trust takes time. Our years of developing ties in some of the state’s most neglected counties has laid the groundwork for us to take the MVP into communities where we can make the biggest impact — not just in the next election, but for decades to come.

While 78% of South Carolina’s nonwhite voting-age population is registered, only half of them regularly vote. An average of 500,000 of the state’s one million registered Blacks (along with 100,000 unregistered citizens), are sitting out the elections. If those “missing voters” were mobilized, it could change everything.

The continuing racial disparities in jobs, housing, health care, poverty, education, and the criminal justice system show that Black lives are devalued in South Carolina. It is not an accident, and it is a problem that won’t fix itself.

Reality check: for decades, incumbent legislators have been allowed to carve political maps to retain their power by packing Black and White voters into racially segregated political districts. This creates safe seats for incumbents but dilutes the effectiveness of Black votes on state policies.

The MVP is working to motivate and sustain Black civic engagement by showing that we can increase the turnout of Black voters by 200,000 in the only political district that cannot be gerrymandered: a statewide race.

The average margin of victory in the last three governor’s races was only 125,877 votes. If our plan works, it would prove to the half-million Black registered nonvoters that if political districts were not racially segregated their vote could change public policy.

By 2022, an energized Black electorate in South Carolina could determine the state’s next governor, attorney general, and superintendent of education.

The 2020 MVP training will prepare activists to organize county-based petitions in 2021 to force a constitutional amendment on the 2022 ballot to end race-based redistricting. It is part of the Network’s Fair Maps campaign to end partisan gerrymandering in South Carolina. See FairMapsSC.com for details.

This year’s MVP campaign is designed to train and sustain county-based teams of activists who understand that to make meaningful change will take commitment and longterm vision.

Training includes a component to involve MVP organizers in the statewide election protection work that the Network has anchored since 2004, when the nation’s first paperless voting system was implemented. MVP volunteers will meet their county’s election director, become credentialed poll watchers, and have the opportunity to participate in their county’s vote certification process.

Volunteer organizers will be trained to help with Census enumeration. With only 57% of citizens counted, South Carolina ranks 44th among states. Each uncounted resident costs our cash-strapped state $15,000 in federal funds this decade.

Last year, we partnered with the new leadership of the NAACP State Conference to test the 2020 MVP to see whether it could effectively be launched statewide. The Memorandum of Understanding was enthusiastically endorsed by the national NAACP office. The plan set our two-county model in place.

As the pandemic worsened, we adjusted recruiting, training, and mobilization strategies to keep organizers and the public safe.

We mailed a letter to young Black voters in our two targeted counties — Saluda and Fairfield — inviting them to join their county MVP team.

It wasn’t until 2018 that majority-Black Fairfield County elected its first Black state representative since Reconstruction.

Ten years earlier, the MVP conducted its first student training at the only high school in Fairfield County. The team registered three times as many new voters than had previously voted. At almost 25%, the county now has the state’s second-highest youth participation rate.

Saluda County is majority-White, and had just 65 young, Black voters in 2018. For decades, the Network has worked with the Riverside CDC, the only enduring civic engagement organization in the county. It prepared us for this campaign.

The level of capacity in this rural county with poor broadband service is requiring a different organizing model than in Fairfield. The differences between the two inform how we are conducting MVP outreach in other counties.

In Saluda and Fairfield counties, the NAACP Branch has partnered with local Network members to support the MVP teams. With their help, we are soliciting community buy-in to help sustain core teams of local activists beyond 2020. We are paying a stipend to trained organizers. The more money we raise, the more boots we can put on the ground.

In both counties, a vibrant organizing core is taking root. Word is getting out that something is happening.

Each week, MVP volunteers are being trained through Zoom sessions, supplemented with socially distanced and masked in-person meetings.

Training includes a short course on democracy and a brief but critical history lesson that explains how our democracy was made — and how we can remake it to be more equitable for a new generation.

The young organizers are excited about leading such a bold and hopeful plan. They are making their calls to other young voters in their county using the State Voices database and an automated Virtual Phone Bank that trained volunteers can access from their phones. When that list is finished, they will begin calling the registered voters their age who didn’t vote. The next round of calls will go to unregistered young people. And when they have contacted and cajoled their peers, they will then begin calling the county’s older citizens.

With organizing underway in the model counties, the MVP is focusing on Richland County, which houses the state capitol as well as two HBCUs.

Just 4,306 out of 27,397 young, Black residents of Richland County voted in 2018.

We can change that. 2020 offers an unprecedented opportunity to reconsider our shared values and transform the institutions that have failed in South Carolina by creating systems that work for everyone, not the select few.

There are no short cuts when it comes to grassroots organizing. Trust takes time. Our years of developing ties in some of the state’s most neglected counties has laid the groundwork for us to take the MVP into communities where we can make the biggest impact — not just in the next election, but for decades to come.

Please VOLUNTEER or DONATE!

MissingVoterProject.com

• • •

On the first day of session, lawmakers pledge bipartisan support for fair maps in SC

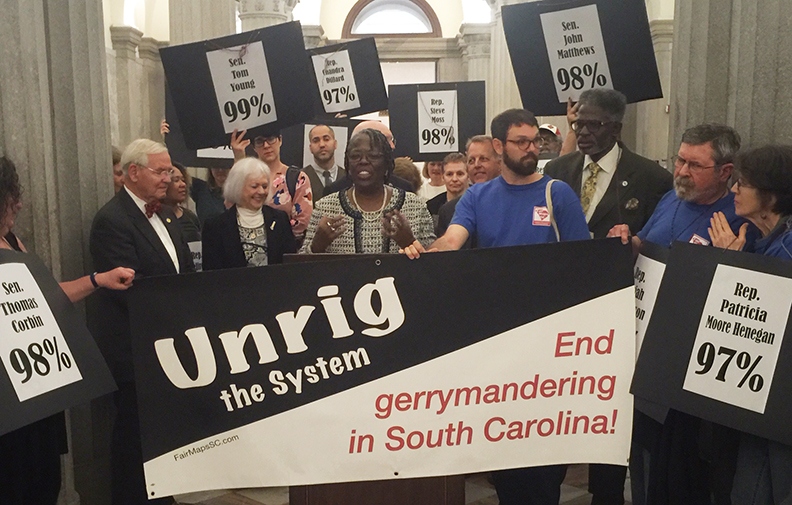

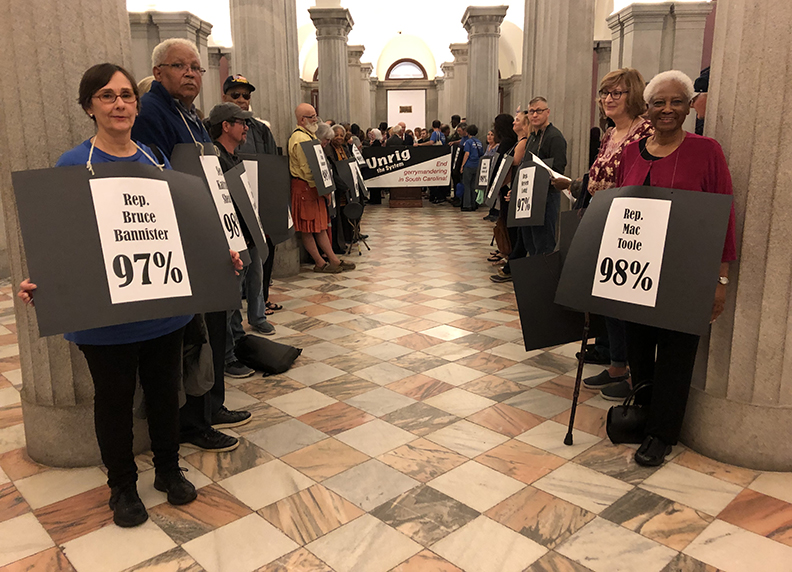

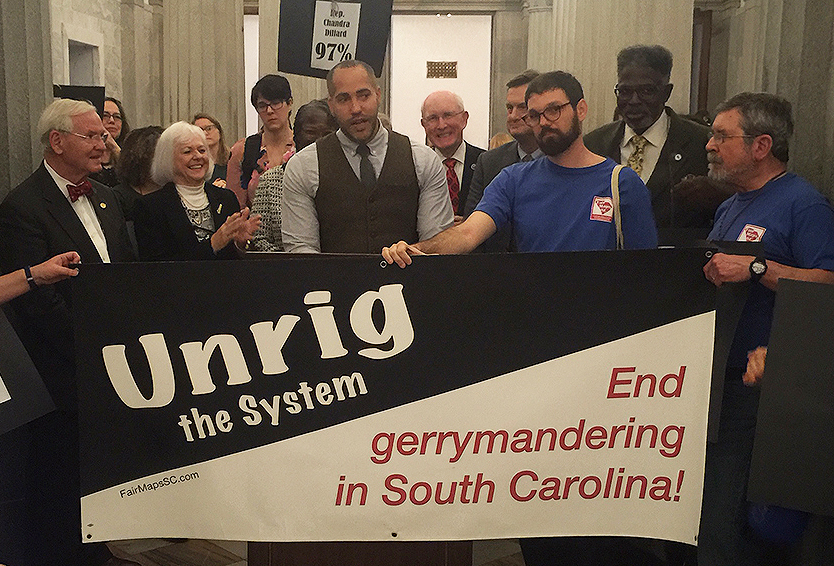

On the first day of the SC 2020 legislative session, fair maps advocates gathered at the State House holding signs with the names of state lawmakers and the percentage by which each won their seats. The original plan to assemble on the front steps of the State House was rained out, but it didn’t dampen the spirits of those who filled the lobby.

On the first day of the SC 2020 legislative session, fair maps advocates gathered at the State House holding signs with the names of state lawmakers and the percentage by which each won their seats. The original plan to assemble on the front steps of the State House was rained out, but it didn’t dampen the spirits of those who filled the lobby.

Some drove hours to be there — from Charleston, Greenville, Rock Hill, and more than a dozen from Horry County, where activists have been working a county-based petition drive for fair maps in South Carolina.

Brian Kasprzyk and his wife, Malle Kasprzyk, drove from Little River. It was a long trip, but worth the drive, he said. On the Fair Maps Facebook group, he posted: “Today was a great day for democracy and fair maps in South Carolina. It was great because 2 republican and 2 Democratic legislators joined together to address the crowd and support redistricting legislation — for the first time.”

Brian Kasprzyk

It’s true. In an unprecedented move, a bipartisan group of SC lawmakers stood in the State House together to make a strong and unified public statement against gerrymandering in South Carolina. Democrats Rep. Gilda Cobb-Hunter and Sen. Mike Fanning joined Republicans Rep. Gary Clary and Sen. Tom Davis at a morning press conference on Jan. 14.

Retired Sen. Phil Leventis made opening comments. In his 32 years as a state lawmaker, he took part in five redistricting sessions. “In 2002, we reapportioned the Senate,” he said, “and before the elections in 2004 it was reapportioned again. I can’t tell you why. But I can tell you it raises questions about the whole process. And the process needs to be fair.”

The system is broken. Fact is, 75 percent of South Carolina voters have only one name on the ballot for House or Senate. Ninety percent of legislative seats were won with an average of 86% of the vote. Just 10 percent of the General Assembly was won by less than 60 percent. That’s 17 seats out of 170.

Competitive districts make winners work to please a majority of the voters, not just the small percent that turns out for the primary.

The task at hand is studying and debating the several proposals that have been filed, and finding common ground that, ultimately, gets politicians out of the business of picking their voters.

The task at hand is studying and debating the several proposals that have been filed, and finding common ground that, ultimately, gets politicians out of the business of picking their voters.

“South Carolina has more problems with gerrymandering than any state in the United States of America,” Sen. Fanning said. “It is not a Republican problem or a Democratic problem; it is a people not having a voice in their government problem. For every solid, safe Republican seat we have a solid, safe Democratic seat. We have created an apartheid here in South Carolina that has divided the voters at the whim of politicians.”

Rep. Cobb-Hunter said, “We all can agree the system is, indeed, rigged.” She vowed to support any fair maps bill that gets traction. “It makes for a better South Carolina, a better governance when all of us who are blessed and highly favored enough to be in these positions when we have to reach out to everybody as opposed to a select group.”

Rep. Clary said, “What we’re talking about here is fundamental fairness. The idea that I, or any other member of the General Assembly, can go in and adjust the line to suit my whim – -to move someone out of my district or to remove a group from my district — is repugnant to me.”

Sen. Davis said, “What we have is a crisis of legitimacy. The idea that I or any other member of the General Assembly can go in and adjust the line to suit my whim – to move someone out of my district or to remove a group from my district is repugnant to me. What we’re talking about is restoring people’s faith in representative government. This is about returning power to the sovereign people.”

Fanning, a former social studies teacher, said he taught civic engagement. “We registered to vote in my class. I made sure my students knew where to vote and when to vote. I had pumped them up, with as much passion as I had inside me. What broke my heart is that when my students came back and said, ‘There was only one name on the ballot. My vote didn’t matter.’ There wasn’t anything I could say to that.

“We have banded together as Republicans and Democrats in the Senate and the House. Each of us has bills, but none has gotten traction because the argument doesn’t belong to us, the argument belongs to the people.”

Preston Anderson has taken that directive to heart. As a volunteer with the Fair Maps SC Coalition has spent months going to events to talk about fair maps and gather signatures for the Richland County petition drive. By now he has talked to hundreds of South Carolinians. “Across the political spectrum, people were very interested in learning more about gerrymandering and the effect it has had on the political situation in South Carolina.”

Fair Maps organizer Preston Anderson

Fair Maps organizer Preston Anderson

Fair Maps volunteers who have been in the field see a steep learning curve ahead. They are finding that a surprising number of voters know little to nothing about gerrymandering and how it corrodes the integrity of South Carolina’s elections. Same goes for lawmakers.

To that end, we gave each of them our handout full of numbers that should alarm anyone who cares about the state of democracy in South Carolina.

For more about the Fair Maps Coalition, (the SC Progressive Network is a member) see FairMapsSC.com.